Key points

- The 2022 Autumn Statement saw the Chancellor promise an extra £3.3bn for the NHS and £1.4bn for capital investment in 2023/24 and 2024/25. In cash terms, spending in 2024/25 will be almost £14bn higher than in 2022/23.

- Much of this additional spending will be needed to meet inflation. After accounting for inflation, real-terms funding in 2024/25 will be £6bn higher than in 2022/23.

- This means that in real terms, core day-to-day spending on the NHS will rise by 2% a year by 2024/25, while capital spending will grow by just 0.2%.

- Overall, the Department of Health and Social Care’s funding settlement will increase by 1.2% a year in real terms over the next 2 years. This is higher than planned at the last Spending Review but far below the 3.6% long-term average growth rate.

- The NHS continues to face rising cost pressures that will erode the spending power of this settlement, with pay being the most significant. Health service inflationary pressures may be higher than the government estimates through the central GDP deflator forecast.

- The different methods used to estimate inflation for the whole economy show that the buying power of this settlement is uncertain. The unknown outcome of future pay negotiations and volatility in the cost of other key inputs add further uncertainty around the actual cost pressures the health care sector will face.

Table 1: Funding levels and growth for the DHSC health budget

Note: Funding excluding COVID-19 and including COVID-19 (in brackets)

| Outturn (cash terms, £bn) |

Planned (cash terms, £bn) |

Compound annual growth rate (CAGR) (real terms, %) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019/20 | 2020/21 | 2021/22 | 2022/23 | 2023/24 | 2024/25 | 2021/22–2024/25 | 2022/23–2024/25 | |

| DHSC total health budget (TDEL), of which: | 140.5 | 144.9 (193.0) |

153.1 (189.8) |

180.2 | 187.9 | 193.0 | 4.8% (-2.5%) |

1.2% |

| Day-to-day spending (RDEL) | 133.5 | 136.3 (180.2) |

144.1 (180.7) |

168.2 | 176.2 | 180.4 | 4.5% (-3.1%) |

1.3% |

| Of which: NHS England |

123.8 |

125.9 (149.5) |

133.7 (150.6) |

152.6 |

160.4 |

165.9 |

4.2% (0.1%) |

2.0% |

| Other health budgets | 9.7 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 15.6 | 15.8 | 14.5 | 8.3% | -5.7% |

| Capital spending (CDEL) | 7.0 | 8.6 (12.7) |

9.0 (9.0) |

12.0 | 11.7 | 12.6 | 8.5% (8.3%) |

0.2% |

Source: Autumn Statement 2022 and OBR Economic and Fiscal Outlook November 2022. Note: numbers in brackets show total health budgets including funding for COVID-19 (sources: PESA July 2022 and 2022/23 Variation to the Financial Directions to NHS England).

Note: Total Departmental Expenditure Limit (TDEL) is the Resource Departmental Expenditure Limit (RDEL) plus the Capital Departmental Expenditure Limit (CDEL). Other health budgets cover wider health spending, including workforce education and training and public health services, and are obtained as the difference between DHSC RDEL and NHS RDEL.

Table 2: Average real-terms growth in DHSC TDEL by administration

| Government | Time period | Annual growth |

|---|---|---|

| Thatcher and Major Conservative governments | 1978/79 to 1996/97 | 3.0% |

| Blair and Brown Labour governments | 1996/97 to 2009/10 | 6.7% |

| Coalition government | 2009/10 to 2014/15 | 1.1% |

| Cameron and May Conservative governments | 2014/15 to 2018/19 | 1.7% |

| Johnson, Truss and Sunak Conservative government | 2019/20 to 2022/23 | 4.9% |

| Sunak Conservative government | 2023/24 to 2024/25 | 1.2% |

| Long-term average (pre-COVID-19) | 1949/50 to 2019/20 | 3.6% |

Source: HMT Autumn Statement 2022 and House of Commons NHS Funding and Expenditure (Briefing paper, January 2019).

Note: The table shows real terms average growth rates for DHSC TDEL spending excluding COVID-19 spending in years 2020/21 and 2021/22, using the GDP deflator. The long-term average is calculated for UK-wide health spending, for which data are available starting from 1949/50.

Table 3: Capital investment in health, £bn

| Cash terms (£bn) | 2022/23 | 2023/24 | 2024/25 | CAGR real terms 2022/23–2024/25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spending Review 2021 | 10.6 | 10.4 | 11.2 | 0.7% |

| Autumn Statement 2022 | 12 | 11.7 | 12.6 | 0.2% |

| Difference | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 0.5% points |

Source: HMT Autumn Statement 2022 and Spending Review 2021, and OBR Economic and Fiscal Outlook November 2022.

However, the latest allocation for capital represents a substantial increase over the previous decade. Capital spending increased on average by 3.2% between 2010 and 2020, almost three times lower than the growth rate over this parliament. In the decade before the pandemic, capital investment was consistently reallocated to support day-to-day running costs in the NHS. The underinvestment in capital infrastructure is the main contributor to the high cost of fixing the backlog of maintenance – the cost of bringing deteriorating assets back into suitable working condition.

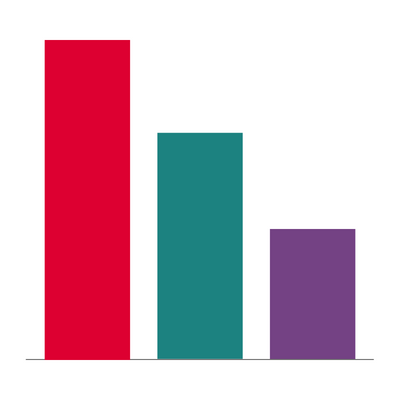

Figure 1

Latest estimates suggest the maintenance backlog for the NHS estate reached £10.2bn (almost £11bn in real terms) in 2021/22, more than twice as high as it was a decade ago (Figure 2). With inflation in the construction sector reaching 10% in September 2022, the cost of clearing the backlog might yet increase further. Around half of the estate backlog is classified as high or significant risk, requiring urgent priority repairs and replacements. This means patients and staff are using outdated facilities and equipment that could be unsafe and lead to poor care.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Uncertainty around cost pressures

There is high uncertainty around the true cost pressures the health care sector is going to face in the next 2 years. One obvious reason is due to staff pay, which makes up almost 70% of NHS providers’ costs, and almost half of the total DHSC budget. Any unfunded pay increase to settle current industrial action would have a significant impact on NHS budgets and implications for services.

There are no published plans for NHS pay beyond this year. If health care staff earnings rise in line with the OBR’s forecast for the whole economy (nominal) earnings, they would increase by 3.5% and 1.6% in each of the next 2 years. However, the ongoing cost-of-living crisis is also likely to have adverse implications for staff morale and retention, particularly after the burnout experienced by many staff during the pandemic. The health care sector is braced for a prolonged period of industrial action and the outcome of this adds uncertainty about earnings growth over the next 2 years.

Another source of uncertainty is the future cost of energy. The Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy estimates that in the year up to September 2022, non-domestic users have seen electricity and gas prices increase by 63% and 124% respectively. Energy costs account for more than 7% of the total cost of running the NHS estate (NHS Digital, Estates Returns Information Collection 2021/22). Hospitals will benefit from the Energy Bill Relief Scheme running until March 2023, and to a lesser extent from the new Energy Bills Discount Scheme over the next 12 months. But as pointed out by the ONS, the extent to which public services are exposed to price increases and will benefit from the scheme are unknown, due to these services using a mix of variable and fixed tariffs.

In addition, NHS leaders have recognised the risk that significant inflation in the construction and raw material markets could erode the value of the capital budget and therefore increase the cost of delivering key capital priorities. They also acknowledge the further volatility expected in these markets, adding to the uncertain outlook.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more