At what level should social care costs be capped?

What different levels of social care cap would mean for people with different levels of wealth

16 July 2021

Key points

- Social care needs more funding, combined with policy action, to help tackle unmet need, raise quality, stabilise the provider market and improve the pay and conditions of those working in the sector.

- Reform is also needed to the way care is paid for, so that people are protected against catastrophic costs. There are indications that the government is moving towards introducing a cap on care costs, with discussions focusing on the level of the cap.

- A cap at any level would be a positive step, but the level at which the cap is set is important. A cap of £50,000 rather than £86,000 (which has been mooted as an option) would have higher costs for the state but reduce the maximum amount that individuals are exposed to. A lower cap would particularly benefit those with lower levels of housing assets, including those living in former ‘red wall’ areas.

Adult social care in England needs fixing. It is underfunded, leaving hundreds of thousands of people without the care they need. Those working in the sector are underpaid and frequently experience poor conditions. The provider market is also financially fragile and struggles to attract the investment needed for innovation. These are all problems that any social care reform plan put forward by the government must address.

But fundamental reform of the way in which we pay for care is also needed. Currently, people are exposed to huge and unpredictable costs. For those with the greatest care needs – at least one in ten people – costs can run into hundreds of thousands of pounds.

Anyone who owns a home, or has more than £23,250 in savings (the so-called ‘upper capital limit’) will need to pay for their own care. This will often mean drawing down on housing wealth until its worth drops below this threshold – at which point the state will start to contribute.

As we explain in our recent analysis, under the current system less wealthy people are most at risk of losing almost everything. Someone with a house worth £125,000 needing 5 years in care could lose more than four-fifths of their wealth. A lifetime cap on care costs of £50,000 would reduce this loss to around a third. Compared to the current system, reform along these lines would disproportionately help those with lower levels of wealth.

The level of the cap

There are indications that the government is moving towards introducing a cap, with discussions focusing on the detail including the level of the cap.

In this analysis we look at the impact of three different cap levels, alongside a more generous means-test, lifting the upper capital limit from £23,250 to £100,000 (as the Dilnot Commission proposed, and government previously accepted):

- £50,000 cap, which would roughly correspond to the central recommendation from the Dilnot Commission in 2011.

- £72,000 cap, which was the level of the cap which was going to be introduced in April 2016 (the cap was subsequently delayed indefinitely), during the passage of the legislation.

- £86,000 cap, which media outlets have reported HM Treasury are arguing for. The rationale is that this is the £72,000 agreed for 2016, uprated to today’s costs.

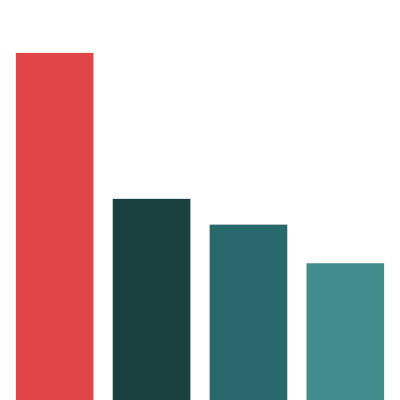

The chart and table below show the spend on care for people with different levels of housing wealth and for different levels of cap. This assumes 5 years of residential care, costing £650 a week, and that the individual has an income of £200 a week.

| No cap | £86k cap | £72k cap | £50k cap | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| House value | Amount spent | % of house value | Amount spent | % of house value | Amount spent | % of house value | Amount spent | % of house value |

| £125k | £103k | 83% | £61k | 49% | £54k | 43% | £42k | 34% |

| £250k | £117k | 47% | £86k | 35% | £72k | 29% | £50k | 20% |

| £500k | £117k | 23% | £86k | 17% | £72k | 14% | £50k | 10% |

This shows that under the current system, someone spending 5 years in a care home with a house worth £125,000 would spend about 83% of their house value on care. With a £50,000 cap (and a £100,000 upper capital limit) this falls to 34%, but this proportion rises as the value of the cap increases. With a £86,000 cap it rises to 49%.

For someone with a £500,000 house, increasing the cap, making it less generous to individuals but cheaper for the state, has much less effect – the proportion spent on care rises from 10% with a £50,000 cap to 17% with a £86,000 cap.

Reducing the value of the cap has the greatest proportionate impact on those with low levels of wealth.

Impact on different types of constituencies

As we showed in a previous article, this has a political dimension. Housing is for most people the main form of wealth. Typically, Labour constituencies have lower median house prices than Conservative constituencies – £190,000 compared with £250,000. But the pattern is very different in areas which the Conservatives gained at (and since) the 2019 General Election – the so-called ‘red wall’ seats, now sometimes referred to as 'blue wall seats'. The median house price in these areas is £160,000, compared with £270,000 in the non-‘red wall’ seats, and below that of Labour seats (£190,000). And home ownership is not atypical in these areas, with the median home ownership rate being around 65% (similar to the national average).

What this means is that, on average, those living in former red wall seats are more at risk of suffering catastrophic losses from social care costs than those in ‘traditional’ Conservative areas. A cap on social care costs would particularly benefit people living in these former 'red wall' constituencies. But increasing the level of the cap has the greatest negative impact in these places.

Conclusion

A cap at any level would be a huge step towards reforming the way in which we pay for social care. But the level at which the cap is set is important. Of course a higher cap would be cheaper for the state – for example, we estimated that a cap of £46,000 would cost around £3.1bn a year in 2023/24; a cap of £78,000 would cost an additional around £1bn a year. But against this are the extra benefits that a lower cap would bring, through reducing the maximum costs that individuals are exposed to. These benefits are greatest for those with lower levels of wealth, including those living in former red wall constituencies.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more