Free personal care: what the Scottish approach to social care would cost in England

30 May 2018

The 1998 Royal Commission on Long-Term Care recommended that the government should meet the costs of personal care in the UK. It argued that since cancer care is available free through the NHS, the same should apply to Alzheimer’s disease. This recommendation was contentious: opponents argued that it was unaffordable. It was rejected in England and Wales, but the newly created Scottish Parliament saw an opportunity to provide a distinctive approach to long-term care policy and proceeded to introduce free personal care (FPC) in 2002.

So is the Scottish system of FPC a worthy policy aspiration for the rest of the UK? Let’s look at how it works.

Scottish funding for personal care in care homes

The challenge of funding a care home place in Scotland is not substantially less than in England.

In care homes, people aged over 65 assessed as requiring personal care receive a weekly payment of £174 to cover personal care costs; a further payment of £79 is made to people who need nursing care (FNC). These payments are made by local authorities and funded by the Scottish Government.

However, when the policy was introduced, the Department of Work and Pensions decided that cash support from local authorities for personal care breached its rules for Attendance Allowance (AA). Therefore, care home residents in Scotland who are eligible for personal care are ineligible for AA (currently worth £85.60 at the top rate).

For self-funders, average care home fees in Scotland in 2016 were £798 (1) per week without nursing care, and £860 per week with nursing care. Therefore, self-funding care home residents in Scotland, like those in England, face a considerable challenge to meet care costs. FPC allowances in Scotland only meet around 25% of the weekly costs of a residential care home. In England, people requiring nursing care receive £158 weekly for the standard rate, and £218 at the higher rate. Further, care home residents in England are eligible for AA.

So what does the challenge of funding personal care look like at a population level? The cost of FPC in care homes to the Scottish Government is made up of weekly payments to around 10,000 self-funding care home residents who would otherwise have to pay full fees. Including the weekly charge for those requiring nursing care, the total cost was £134m in 2015-16. Total spending by local authorities on care homes in the same year was £667m. This was mostly for publicly funded residents; FPC and FNC spending accounted for less than 20% of the total.

On a simple population ratio, the equivalent cost for England would be £1.4bn. But this may overstate this cost given that nursing care support is more generous in England and AA payments are not available to FPC clients in Scottish care homes. On the other hand, average wealth per household in England slightly exceeds that in Scotland, leading to a higher proportion of self-funders in England and Scotland, though this is difficult to judge without detailed knowledge of the wealth distributions in the two countries.

Scottish funding for personal care at home

For care at home, in Scotland the situation is different. For those aged over 65 assessed as needing personal care, the local authority has a duty to provide care and is not allowed to charge for it, even if the client could afford to pay. The care may be provided directly, commissioned from a private company, or the person may be given a cash sum to pay for ‘Self-Directed Support’. And in the Highlands, where care for older people has been organised through the NHS since 2012, the support may also come from NHS staff.

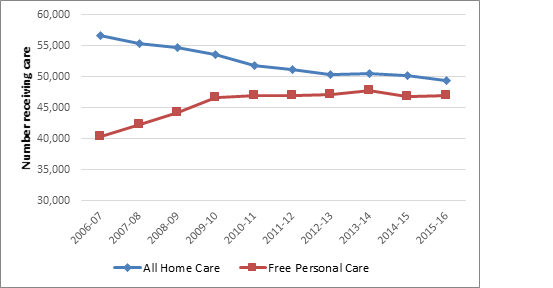

The chart below clearly illustrates how pressure on local authority budgets has squeezed the number of those aged 65+ receiving non-personal care at home.

In 2006-07, 57,000 of this group received some form of care at home (around 1.8% of those aged 65+ in Scotland). Around 70% of these were being given FPC. Numbers receiving FPC has levelled out at around 47,000 in recent years, but the overall number of home care clients has fallen to around 49,000, so that by 2016-16 FPC accounted for about 96% of all those receiving home care aged 65+.

The vast majority of older people currently receiving care at home in Scotland do so because they have been assessed as requiring personal care. Since FPC is a legal requirement, financially constrained local authorities have cut back on other forms of care.

Source: Scottish Government

Squeezed local authority budgets have reduced overall care for older people, but because FPC is enshrined in law, it cannot be withdrawn. This focus on personal care has led to an increase in average weekly hours per client from 9.1 in 2007 to 11.7 in 2017.

It is difficult to draw direct comparisons with England: the latest community care statistics suggest that 205,000 clients aged over 65 had received local authority support in 2016 comprising a mixture of personal budget and commissioned support. A further 43,000 received direct payments and/or community support. Scotland lags far behind England in the provision of cash payments to buy care services. Local authorities still provide direct care services through their social work departments, though their share of the market has fallen from 73% in 2007 to 47% in 2017.

These data can also be used to estimate the additional costs of introducing FPC to England. Based on population shares, a further 240,000 clients would be receiving home care in England if it was being delivered at the same intensity as in Scotland. Based on Scottish government estimates of the costs of providing personal care at home, the annual costs of the 240,000 additional care clients in England would be around £2.4bn.

What does the Scottish experience of FPC mean for the rest of the UK?

It certainly attracts fewer negative headlines than that in England, but it seems to cost more, though the cost differences due specifically to personal care are difficult to disentangle when the health and social care systems in Scotland and England are diverging.

In relation to social care, the main cause of cost divergence lies with higher levels of support in Scotland for those receiving personal care at home. From the previous arguments, the extra costs to the care budget in England may be around £3.8bn. This fits within the range estimated by the Health Foundation for the cost of introducing free personal care in 2015/16 of between £3.1bn and £6.7bn, with a central estimate of £4.3bn (2). However, a broader view should take account of potential savings for the health budget.

Would the UK government be prepared to adopt FPC in England? The arguments against include costs, though these need to be rigorously assessed as outlined above. In addition, since it supports a universal benefit, a FPC policy provides free services to some who could afford to pay. Which brings us back to the equity argument about the contrast between those health conditions, such as cancer, which the government is willing to fully insure against and those, such as dementia, where government funding support is much more limited. These arguments stand in stark contrast, but the UK political system has repeatedly failed to generate any significant change in England to a system which is generally viewed as fundamentally unfair and unsustainable.

Professor David Bell (@DavidNFBell) is a Professor in Economics at the University of Stirling.

1. In 2018/19 real terms (as are all following quoted financial figures)

2. In 2018-19 prices: https://www.health.org.uk/publication/social-care-funding-options

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more