How are total triage and remote consultation affecting prescribing patterns?

10 December 2020

Key points

- The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in the rapid and widescale adoption of online and digital tools such as total triage and remote consultations. However, there are concerns that the prescribing behaviour of clinicians may be negatively affected during a remote consultation by a lack of visual cues and the inability to physically examine a patient ‘in person’.

- Here we focus on the impacts of total triage and remote consultation on prescribing patterns for commonly prescribed medicines known to have impacts on public health or patient safety – antibiotics, opioid analgesics and antidepressant medicines. We use a synthetic control to compare prescribing rates at practices that are using the askmyGP model of total triage and remote consultations with those that are not using any digital tools.

- We found no significant evidence of any effect of the askmyGP model on prescribing rates for these medicines during 2019.

- After the pandemic began in March 2020, all GP practices in England were encouraged to start using total triage and remote consultation. As a result, we can no longer compare between practices using these approaches and those that are not. Instead we looked at prescribing rates in GP practices that were ‘early adopters’ of the askmyGP model before the pandemic began.

- Among these early adopter practices, the rate of antibiotic prescribing fell dramatically in March to August 2020 compared with the same period the year before. This was in line with national trends and likely reflects an increased focus on hand hygiene, social distancing, and reduced travel leading to lower disease transmission.

- The March to August year-on-year rate of opioid prescribing among the early adopters decreased in 2018 and 2019 and showed no significant change during the pandemic in 2020. The March to August year-on-year rate of antidepressant prescribing among the early adopters increased in 2018, 2019 and 2020. These results are in line with national trends.

- Our analysis has some limitations. We looked at a single provider of software for total triage and remote consultations and results may not be generalisable. Because the analysis is at practice level, we cannot take account of the characteristics of individual patients receiving each prescription, the consultation model used, or why the patient needed the prescription.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in the rapid and widescale adoption of total triage and remote consultations (by telephone, video or online) at GP practices. It is possible to offer total triage entirely by telephone, but COVID-19 has further spurred many practices to use online consultation systems to gather information and support the triage of patient contacts – ‘total digital triage’. The benefits of this may include further increasing efficiency, offering faster access to care and creating more time for GPs to focus on patients who are vulnerable or need extra care.

Almost 9 in 10 GPs think that the ‘greater use of digital technology should be retained in the longer term’. Digital-first primary care – where patients can easily access the advice, support and treatment they need using digital and online tools – is part of the long-term vision for NHS England. However, some GPs have expressed concern that ‘the pendulum has swung too far’ and that remote consultations may compromise patient safety and professional satisfaction. More research is required to inform the safe implementation of total triage and remote consultation.

This analysis looks at the early impact of these tools on the prescribing patterns for three common types of medication – antibiotics, opioid analgesics and antidepressants. We compare prescribing rates at practices using and not using total triage and remote consultation. We focus on this during 2019 because since the beginning of the pandemic most practices have adopted total triage and remote consultation. During the pandemic, between March and August 2020, we describe the trends in prescribing rates at the early adopter practices, which by then had been using digital approaches for some time.

Why are prescription patterns for some medicines a particular concern?

Concerns have been raised that patterns of prescribing may differ between remote and face-to-face consultations. This may be due, for example, to the inability to physically examine a patient in person during a remote consultation, or a lack of visual cues.

It has been suggested anecdotally that more ‘just in case’ prescriptions for antibiotics may have been issued during COVID-19 as a result of total triage and remote consultation. Prescribing patterns for antibiotics are of concern as inappropriate prescribing may contribute to antimicrobial resistance (AMR) – a threat to public health adding to the global rise of drug resistant infections. The UK government has set out a 20-year vision to contain AMR by 2040. Although antibiotic prescribing has declined between 2014 and 2018, studies reveal that 20% of antibiotic prescribing is still inappropriate.

There are also concerns relating to patient safety for prescribing other medicines such as opioid analgesics or antidepressants, which may cause dependence or withdrawal. The number of prescriptions for opioid analgesics in England decreased between 2017 and 2018 after more than doubling between 1998 and 2016. However, in 2019, opioid analgesics still remained in the top 10 most prescribed medicine classes in primary care by spend. They are effective for acute pain but have also been widely prescribed for chronic pain, despite limited clinical evidence of benefit. A study in Norway found that opioid analgesics were more commonly prescribed to older patients during remote consultations than during face-to-face consultations. The number of prescriptions for antidepressants has almost doubled in the past decade from 36 million in 2008 to 71 million in 2018. In 2019, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors – a type of antidepressant – were in the top 10 most prescribed medicine classes in primary care by volume.

What data did we look at?

We examined 209 practices that started using askmyGP, an NHS-approved digital platform, from August 2018 onwards. askmyGP offers total digital triage and remote consultation to practices across the UK. Patients make contact with the practice via a link from the practice website. Non-digital users are taken through the same process by practice staff over the phone. Clinicians and staff then prioritise and deliver care face-to-face at home, at the surgery or by telephone, online or video consultation, according to the patient’s preference and needs.

We obtained data on prescribing patterns from OpenPrescribing – a research project funded by the Health Foundation – which provides a search interface using anonymised prescribing data published by the NHS in England. We extracted GP practice-level antibiotic, opioid analgesic and antidepressant data on the total number of items prescribed and dispensed for patients registered at the 209 askmyGP practices and all other GP practices in England open between September 2016 and August 2020.

Our method relied on identifying 19 of the 209 askmyGP practices as ‘early adopters’ – those using askmyGP before mid-2019, well before the COVID-19 pandemic began. We also identified 133 ‘late adopters’ – those adopting askmyGP only after the pandemic began. We structured our analysis into 2 phases. First, we estimated the pre-pandemic impact of total triage and remote consultation on prescribing patterns by compared prescribing rates between these two groups in 2019, when only the early adopters were using the askmyGP model. Second, we described how prescribing patterns changed in the early adopter practices during the COVID-19 pandemic from March 2020 to August 2020. We also compared prescribing rates in both groups with national estimates based on all practices in England.

We used a synthetic control model to estimate the pre-pandemic impacts. The basic aim of the synthetic control approach is simple: to compare the early adopters to a set of practices that are similar in all respects except for the fact that they do not use the askmyGP model. We created this synthetic control by selecting from the late adopters in such a way that the resulting synthetic control closely resembled the early adopters in terms of prescribing rates and key demographic, socioeconomic, clinical, administrative and geographical characteristics in the period just before they started using the askmyGP model. By continuing to chart prescribing rates in the synthetic control after the early adopters started using the askmyGP model, we were able to compare its rates to those in the early adopters. See this briefing for another example of the synthetic control approach.

The early and late adopter askmyGP practices have similar characteristics and are broadly representative of national trends in terms of number, sex and education of patients. However, 20% of patients in askmyGP practices are older than 65 years compared with 18% nationally, only 7% of patients live in the most deprived fifth of areas and only 9% are of black and minority ethnicity compared with 16% nationally. 58% of askmyGP practices are in urban areas compared with 46% nationally, 24% are in small towns compared with 40% nationally, and the remaining 18% are in rural areas compared with 13% nationally.

What happened prior to the pandemic?

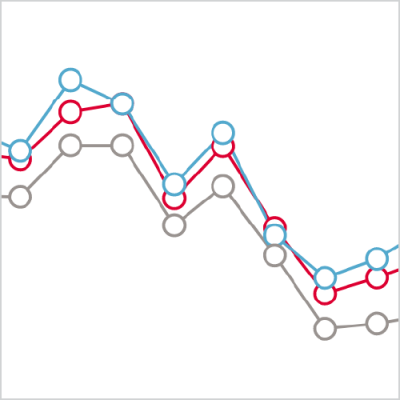

Before the early adopters started using askmyGP from September 2018 onwards, the average rate of antibiotic prescribing was broadly similar among late and early adopters (Figure 1, panel 1 compares early and late adopters). During 2019, when only the early adopters were using askmyGP, there is a slight increase in the average rate of antibiotic prescribing in the early adopters compared with the late adopters between March and September. To check that this difference is real, and not the result of chance alone, we created a synthetic control. The risk-adjusted difference in the rate of antibiotic prescribing between the early adopters and the synthetic control during 2019 was not significant (average treatment effect [ATT] = 0.61 prescriptions/1,000 patients per month, 95% confidence interval [CI] = -2.2 to 4.9, p=0.534) (Figure 1, panel 2 compares early adopters and the synthetic control).

Figure 1.

We also found no significant differences in the risk-adjusted rates of opioid analgesic prescribing (ATT = 0.31 prescriptions/1,000 patients per month, 95% CI = - 3.1 to 2.8, p=0.534), or antidepressant prescribing (ATT = -0.28 prescriptions/1,000 patients per month, 95% CI = -5.5 to 4.4, p=0.602), between the early adopters and the synthetic control during 2019.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

The average rates of antidepressant, opioid analgesic and antidepressant prescribing at the askmyGP practices are consistently higher than the national average for practices in England throughout our analysis period. This likely reflects differences between the demographic, socioeconomic and health characteristics of the patients in the askmyGP practices compared with the average for all practices in England. In particular in the askmyGP practices, there is an over-representation of patients older than 65 years, who are known to need more antibiotic prescriptions.

What happened during the pandemic?

The national average rate of antibiotic prescribing between March and August fell year on year from 2018 to 2020 – most markedly with a significant decrease of 10.3% (95% CI = -21.5 to -1.1) in 2020 compared with 2019. The year on year changes in antibiotic prescribing in the early adopters were not significantly different to national trends – despite an average increase of 1.3% in 2019 compared with 2018, the 95% confidence interval ranges from -3.1% to 5.7% and thus overlaps with the national estimate for this period.

The rate of opioid analgesic prescribing among the early adopters broadly reflects national trends with small year-on-year decreases in 2018 and 2019, and no statistically significant difference in 2020. The year-on-year rate of antidepressant prescribing among the early adopters reflects national trends with successive increases in 2018, 2019 and 2020.

Figure 4.

Discussion

Despite a slight increase in the average rate of antibiotic prescribing among the early adopters compared with the late adopters in mid-2019, there was insufficient evidence to conclude that the askmyGP model of total triage and remote consulting had a significant impact on antibiotic prescribing during the period of this analysis. There was also no significant evidence of any impact of total triage and remote consultation on prescribing rates for opioid analgesics and antidepressants in 2019.

Prescribing rates for antibiotics decreased markedly during the pandemic both nationally and in the early adopters compared with the same period in 2019. This is in line with evidence reported elsewhere that may reflect an increased focus on hand hygiene, social distancing, and reduced national and international travel leading to lower disease transmission generally.

Our study indicates small to negligible year-on-year decreases in rates of opioid prescribing and steady increases in rates of antidepressant prescribing among the early adopters. These results are in line with national trends, notably during 2019 and 2020, when the early adopters had started using total triage and remote consultation, suggesting no evidence of these changes on prescribing patterns for these medicines.

However, our analysis has some limitations. Firstly, we looked at a single provider of software for total triage and remote consultations with practices that are skewed towards patients living in urban areas, with low proportions of people from a black and minority ethnic background and a slightly older population. Therefore, results will not necessarily be generalisable to other providers. Secondly, we are not able to differentiate between impacts due to total triage and those due to remote consultation. Thirdly, because the analysis is at practice level, we cannot take account of the characteristics of individual patients receiving each prescription, the consultation model used, or why the patient needed the prescription. Factors such as patient age, gender and ethnicity and long-term conditions can affect prescribing. Finally, during the pandemic, changes to prescribing rates will have depended on a complex set of interactions relating to changes in the way the NHS operates, changes in patient behaviours and the underlying health needs of the population. Hence, our findings of no significant impacts in 2019, before the pandemic, may no longer be relevant as we go forward.

Future work

More studies are required to inform the safe implementation of total triage and remote consultation to ensure that there are no unintended negative impacts on prescribing patterns for antibiotics, opioid analgesics, antidepressants or other medicines. This high-level overview will inform more granular analysis of patient-level data currently being undertaken by the Improvement Analytics Unit.

Acknowledgements

We thank Salvie Ltd. for sharing data for this analysis.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more