Using local authority estimates has important implications for policy. We look at how these estimates are used in the indicator, as well as how they compare to other measures of geographical inequalities in healthy life expectancy.

Construction of the healthy life expectancy indicator

Taking a broader range of local authorities, rather than the extremes of highest and lowest, helps to account for outliers with potentially unique circumstances. For example, in 2017–19 a girl born in the Orkney Islands was expected to have 75.1 years of good health, compared to a girl born in Blackpool with a healthy life expectancy of 55.3 years. As the extreme values, these may be outliers in some form. Creating an average of the top and bottom 10% mitigates against this. However, this averaging also hides the scale of variation across local authorities. It would be possible for the gap between the highest and lowest local authority to widen even if the average gap reduces.

The healthy life expectancy gap has also remained relatively stable since 2009–11, with little change in the composition of the local authorities in the 10% with highest and lowest outcomes. This suggests that there is little volatility in the indicator. However, each data point is a 3-year average, meaning that we would not expect significant shifts in the metric from year to year. There is also a 2-year lag before publication of the statistics, for instance 2018–20 data are available in March 2022. We will therefore not know until 2033 whether the government’s ambition to narrow the gap between areas has been met. If we plan to assess progress in 2030 (using data for the period 2026–28), this leaves the government with only 6 years (ie now until 2028) to effect change.

Comparing between local authorities

Often inequalities in healthy life expectancy are measured on the basis of variation in health across very small local areas of around 1,500 people. One example of such a statistic ranks those small local areas by their level of deprivation. On that basis, for women in England there is a gap of nearly 20 years of healthy life expectancy between those in the most and least deprived 10% of small local areas.

Averaging outcomes within local authorities also hides a lot of variation. For instance, using data from 2009–13 on healthy life expectancy by middle layer super output area (MSOA) – small areas of 7,200 people – the range within Westminster Council (12.6 years) is bigger than the range across the country (10.7 years).

This highlights a key flaw with this measure: if targets typically drive efforts to improve what is being measured, then many of the areas with the worst health are liable to miss out. It is in theory possible to meet the levelling up target without the health of a lot of the MSOAs with the worst health experiencing any improvement.

The availability of published data prevents a timelier analysis, but we can use older data (only available for England) to illustrate the point.

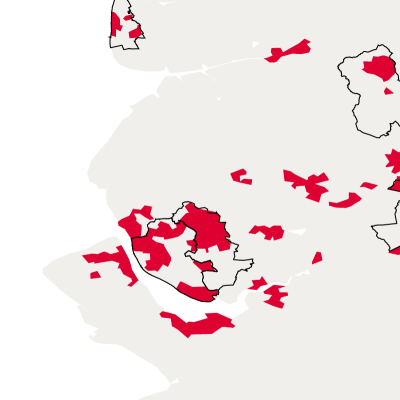

The map looks at average healthy life expectancy for 2009–13 in England. Areas in the 10% of MSOAs in England with the lowest healthy life expectancy are coloured in red. The 10% of local authorities with the lowest healthy life expectancy are outlined in black. As the map shows, there are considerable areas of poor health outside the bottom 10% of local authority areas: for example, in Sheffield, Nottingham and parts of the North East.

These smaller areas would not factor into the England-based target, and we would expect a similar pattern when constructed across the whole of the UK. Measuring at a lower geographical level (such as MSOAs) would focus efforts on smaller local areas with the poorest health in England, which are often not in the local authority areas with the lowest healthy life expectancy (when taken as a whole). Many of the smaller areas with the worst health are in local authorities in which other small areas have good health, bringing the overall average up.