City mayors can play a key role in improving our health

30 April 2021

Key points

- Metro mayors have influence over what makes us healthy: jobs, skills, planning, housing, transport and air pollution.

- There are longstanding health inequalities in these areas across England, many of which have been highlighted by the pandemic.

- These inequalities occur both between and within city regions.

- To improve our health, mayors must focus on boosting skills and jobs, creating better quality homes and enabling healthier transport options.

The upcoming metro mayor elections on 6 May present an important opportunity to make a difference to the health of people living in eight areas of England: Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, Greater London, Greater Manchester, Liverpool City Region, Tees Valley West Midlands, West of England, and West Yorkshire.

Even before the pandemic highlighted stark health inequalities, there were already significant regional differences in how long people could expect to live. For example, men’s life expectancy in Greater Manchester is almost 2 years less than in England as a whole. Within city regions these disparities are even more pronounced – for instance, men in Trafford typically live almost 4 years longer than men in nearby Manchester.

Metro mayors have significant power over many aspects of the lives of the 20 million residents living in their regions. Within their direct influence are areas including skills training (such as the adult skills budget and apprenticeship programmes in most areas), housing options (including powers over strategic planning), air pollution and local means of transport (including bus franchising).

The Health Foundation’s research shows that these areas – work, education, housing, travel and environment – are all important determinants of people’s health. Here we set out the trends in these determinants of health for the eight metropolitan areas, which are soon to elect their mayor for the next 4 years and highlight some policies for priority action.

The current health of city regions

Prior to the pandemic there were significant differences in how long people can expect to live in good health both between city regions and within them, as set out in Figure 1.

Figure 1

In the West Midlands, men can expect to live 3.9 fewer years of good health than the average for England (healthy life expectancy at birth of 59.5 years compared with 63.4 years) – but greater inequality lies within the combined authority. The healthy life expectancy of a man living in Sandwell is 8.2 years lower than a man living in Solihull, for instance.

COVID-19 has caused excess deaths in all city regions, ranging from 13.1% in the West of England and Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, to 34.6% in London. Yet again there has been significant variance in excess deaths within regions, with rates as low as 2% in Cambridge and 16.4% in parts of London, but as high as 58.2% in other parts of London and 32.1% in the West Midlands. While the scale of deaths reflects a number of factors, existing poor health places people at risk of more severe symptoms.

Naturally, each metro area is faced with different pressing priorities. As we emerge from the pandemic, taking the right action at a local level can help to improve our health and reduce inequalities in future. Below we focus on three key policy areas where metro mayors have the power to improve public health.

Priority one: boosting skills and jobs

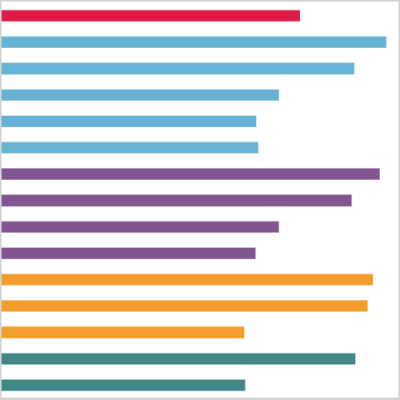

Prior to the pandemic, overall employment rates in Greater Manchester, Liverpool City Region, the West Midlands, the Tees Valley and West Yorkshire lagged behind the rest of England. As Figure 2 shows, it is specific local authorities within each of those regions with lower employment, so creating jobs in those areas was a priority. However, since the start of the pandemic unemployment has risen in all city regions. Between November 2019 and November 2020, the biggest comparative increases in unemployment benefit claimant rates were seen in London (4.9 percentage point increase in the share of the working age population in receipt of benefits), Greater Manchester and the West Midlands (4.1 percentage point increase).

As Figure 2 shows, averages also mask greater rises in unemployment in local areas within city regions. For instance, while Richmond in London has only seen a 2.9 percentage point increase in Universal Credit claimants as a share of the working age population, Newham has seen an increase of 7.2 percentage points.

Figure 2

While it’s important for mayors to do what they can to increase employment rates, simply creating jobs is not enough to improve health. Jobs need to be good quality, secure and well paid. At the moment, these jobs typically go to people with higher qualifications and skills – another area where there is significant geographic inequality. While London has one of the highest average rates of high qualifications (50.1% compared to 48.9% in England as a whole), 11.5% more people in Richmond are educated to degree level than in nearby Lambeth.

Mayors should also support programmes designed to improve the skills of the workforce, in order to make better quality jobs more accessible – particularly in regions hit hardest by the pandemic, where people will need to retrain to obtain new jobs.

Priority two: creating better quality homes

Housing and planning must be a priority for all mayors, but particularly those in London, Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, the West of England, and some parts of Greater Manchester and the West Midlands, where home ownership is less affordable than the rest of England. People living in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough and the West of England can expect properties to cost more than 8 times their gross annual salary, and in London it is 13 times.

An inability to access home ownership has led to more families living in the private rented sector. Renting in the private sector tends to be more expensive than social sector rent or the cost of mortgages for homeowners. High housing costs can impact health by creating financial strain, which can cause stress and can also increase pressure on family budgets, restricting the ability to live a healthy life. Likewise, unaffordable housing can influence health through the quality issues associated with poor living conditions. Overcrowding, for example, is linked to greater spread of diseases – including COVID-19 – and insecure accommodation can affect people’s mental health, wellbeing and sense of stability in life.

Unaffordable and insecure housing can also lead to homelessness, which is comparatively high in London, Cambridgeshire and Peterborough and the West Midlands.

Figure 3

To improve housing and planning, mayors must work to build more affordable homes that better facilitate healthy living, including by working with Directors of Public Health to utilise their expertise to work with urban planning and housing departments.

Mayors can also use the mandate and political capital of their office to ensure a strategic approach across their entire region, as well as ensuring proposed developments meet the combined needs of local communities.

As support for homeless people during the pandemic comes to an end, mayors must develop a comprehensive homelessness plan, from supporting people wanting to escape rough sleeping, to providing appropriate financial support to help prevent evictions in the first place.

Priority three: enabling more affordable and accessible public transport systems and encouraging active travel

Improving transport and tackling air pollution must be a priority for the country as a whole. Transport systems affect our health in a number of ways: they can help improve health by getting people to work, school, hospital and shops along with leisure activities and facilitating social lives. Active transport can improve our physical health and mental health. Transport systems are also key contributors to local air pollution, with those more reliant on private vehicles tending to create more pollution.

As with most of England, active transport levels – indicated here by people walking for at least 10 minutes at a time, or cycling more than five times a week – were lowest in Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire and the West Midlands. The highest levels of active travel were in London and the West of England.

Figure 4

Mayors should focus on both improving public transport systems and embedding green and active transport into long-term planning and design. It is important that public transport systems are designed to be accessible and affordable. They must also support those most excluded from access to services, social activities or job opportunities by a lack of transport options. Taking a strategic approach across each metro region can ensure that bus and train provision is complementary to walking and cycling routes, to help promote active transport and increase physical activity levels.

Conclusion

The metro mayor elections provide an opportunity to improve health and reduce inequalities within city regions. Devolved powers mean that mayors can play an important role in taking a system-wide approach, integrating skills and jobs, housing and planning, transport and environmental health. It’s critical that the newly elected mayors put people’s long-term health and wellbeing at the heart of their roles, by ensuring that their residents’ employment, homes and local environments all contribute positively to their health.

Further reading

Download the data on health outcomes and determinants of health

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more