Social care funding: public perceptions and preferences

10 October 2019

Adult social care in England needs reform – and has done for decades. But while reform has been identified as a priority for several governments, it always seems to be delayed.

Over recent years the issue has risen up the policy agenda – with a flurry of announcements over the past few weeks. The government is promising that a white paper is imminent, and the Shadow Chancellor recently committed the Labour Party to free personal care in England, similar to the model already operating in Scotland.

Whatever reforms are proposed, one thing is certain: funding will be at the heart of the debate.

Failures in funding

Unlike the NHS, social care is means-tested, not free at the point of use. To receive publicly funded adult social care, people first need to be assessed as needing care and then they must have an income, savings and assets below the means-tested threshold (currently set at £23,250). Publicly funded help is only available to those who pass both the needs and the means test.

The 2010 Dilnot Commission explored how a fair, affordable and sustainable funding system for social care could be delivered in England. It highlighted the fundamental fault line with the current means-tested system: it fails to protect people from potentially ‘catastrophic’ care costs, because risk is not shared across the population. One in ten people face the prospect of care costs of over £100,000. As individuals, we can’t insure against this risk and unless we have low income and assets, the state won’t help.

This is a market and government failure. And it continues in part due to limited public understanding of social care. Almost half of the public (47%) think social care is free at the point of need.

Public understanding as a barrier to reform

When the current social care system is explained to members of the public, it’s very unpopular and recognised as deeply flawed. And the unfairness of the current system is not the only problem that needs to be addressed. There are also major issues with the sustainability of providers, workforce, quality and access to care.

Addressing all these issues amounts to a programme of major reform, requiring significant levels of additional funding. But if the government is to successfully reform social care, it needs to be confident that its plans will garner public support.

In the 2017 General Election, Theresa May put forward a package of complex reforms which involved an upper and lower limit on contributions and changed the range of people’s assets included in the means test. Overall that package was more generous than the current system, adding around £5bn to the cost of social care by 2020/21. But it was dubbed the ‘dementia tax’ by opposition parties, and polling data suggested that the public outcry contributed to a sharp decline in support for the Conservatives.

If social care reform is to be successful, it needs to be comprehensive, tackling the range of problems facing the system – but how it’s funded needs to align with public preferences.

Exploring public preferences for social care funding

The Health Foundation commissioned RAND Europe to undertake new research to explore both what the public understand about social care funding, and what options for funding they prefer.

The findings reiterate people’s lack of knowledge about how social care is funded. There were low levels of understanding of how social care is paid for currently and the extent to which people buy it for themselves (or their relatives).

At the heart of the research, RAND conducted a discrete choice experiment with 2,700 adults across the UK. To our knowledge this is the first time such a detailed approach has been taken to analysing funding preferences for social care. The discrete choice approach differs from classic opinion polling as it presents people with a series of choices and trade-offs to select between, in order to draw out underlying preferences between different options. In this study the questions and options focused on how additional funds would be raised in future.

A strong and clear finding is that a majority among all sections of the public – across age groups, income groups, employment status, health status and the four countries of the UK – see adult social care as a collective responsibility. They would like additional funding for adult social care to be raised in the same way as additional funding for the NHS, collectively and progressively. This would mean through tax or mandatory insurance, not by increasing out-of-pocket payments or voluntary insurance. And there is some preference for ring-fencing any additional taxes to be spent only on the NHS and adult social care.

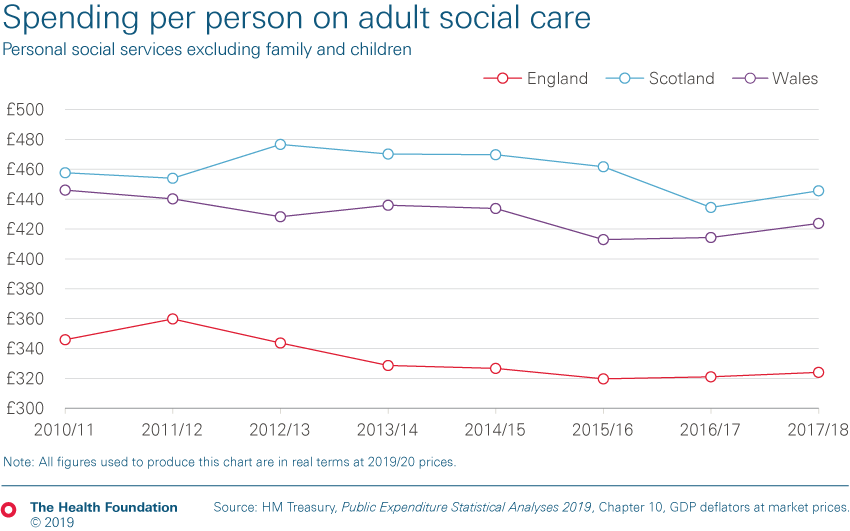

The degree of convergence in public preferences found in the study is interesting at a time when there is much talk of a divided nation. While our recent analysis found a widening gap in adult social care spending per person across the different countries of the UK, the RAND study highlights very similar public preferences across the UK for further funding.

Improving the social care funding system will be a challenge but policy is more likely to succeed if it aligns with public preferences. This research shows a remarkable degree of consistency among all sections of society for further funding for social care to be collective and progressive.

Anita Charlesworth (@AnitaCTHF) is Director of Research and Economics at the Health Foundation.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more