A worrying cycle of pressure for GPs in deprived areas

8 May 2019

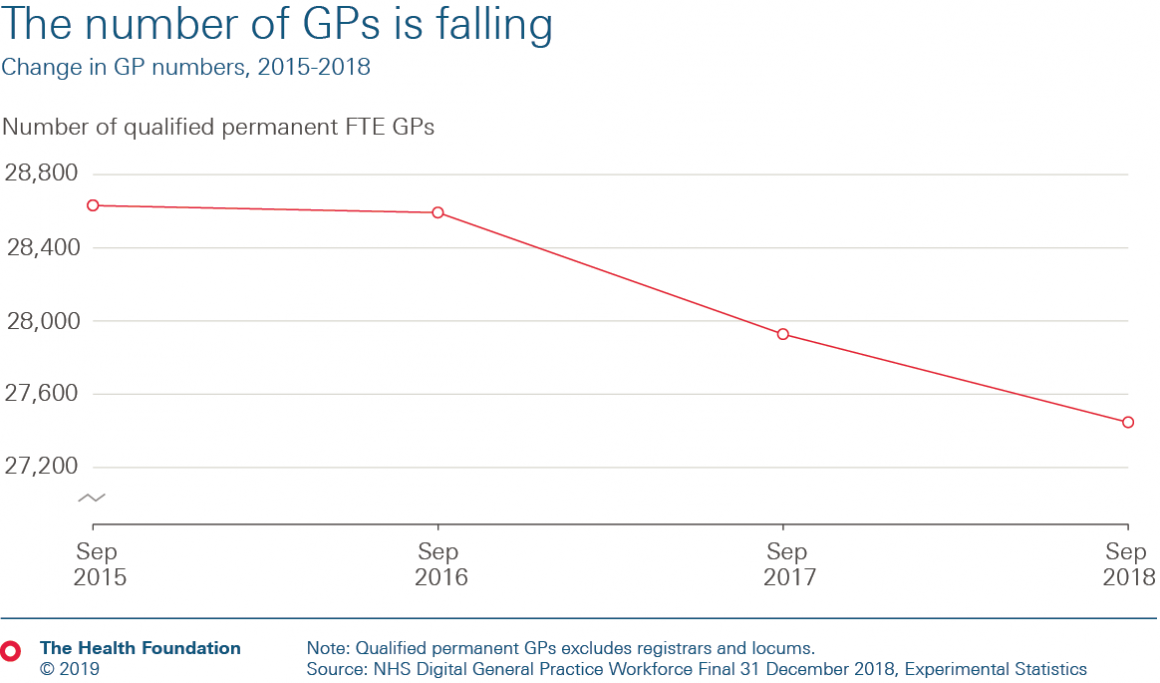

The number of full-time equivalent GPs is falling. Data released from NHS Digital in April show a 4% reduction in the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) qualified permanent GPs between September 2015 and September 2018, meaning 1,180 fewer GPs.

But the crisis in GP numbers is not new.

Despite a very public pledge in NHS England's 2016 General Practice Forward View to recruit an additional 5,000 GPs by 2020, quite the reverse has happened. At face value, the April stats are concerning. Bring deprivation and health need in to the picture, and the landscape becomes bleaker still.

These falling GP numbers come at a time of population growth – the number of people registering at GP practices has increased by 3% over the same period. The result is more patients per qualified permanent GP from an average of 2,000 to 2,160 – an increase of 8% over three years.

That’s on the back of a decade of growth in GP workload. Hobbs et al estimate that workload rose by 16% between 2007 and 2014, the years immediately preceding these data. More patients doesn’t just mean greater demand for appointments. It means more paperwork, test results and administrative work too.

Little wonder that concerns are being raised over the health and wellbeing of the GP workforce. The most recent Commonwealth Fund survey from 2015 showed that UK GPs were the 'most stressed in the West' – one in five reported that they had been made ill by work stress within the past year.

With more than one in three GPs saying they plan to leave the profession within the next five years, the vicious cycle of falling GP numbers driving increased workload is clear. Combine that with rising patient numbers and need, and the mix becomes even tougher.

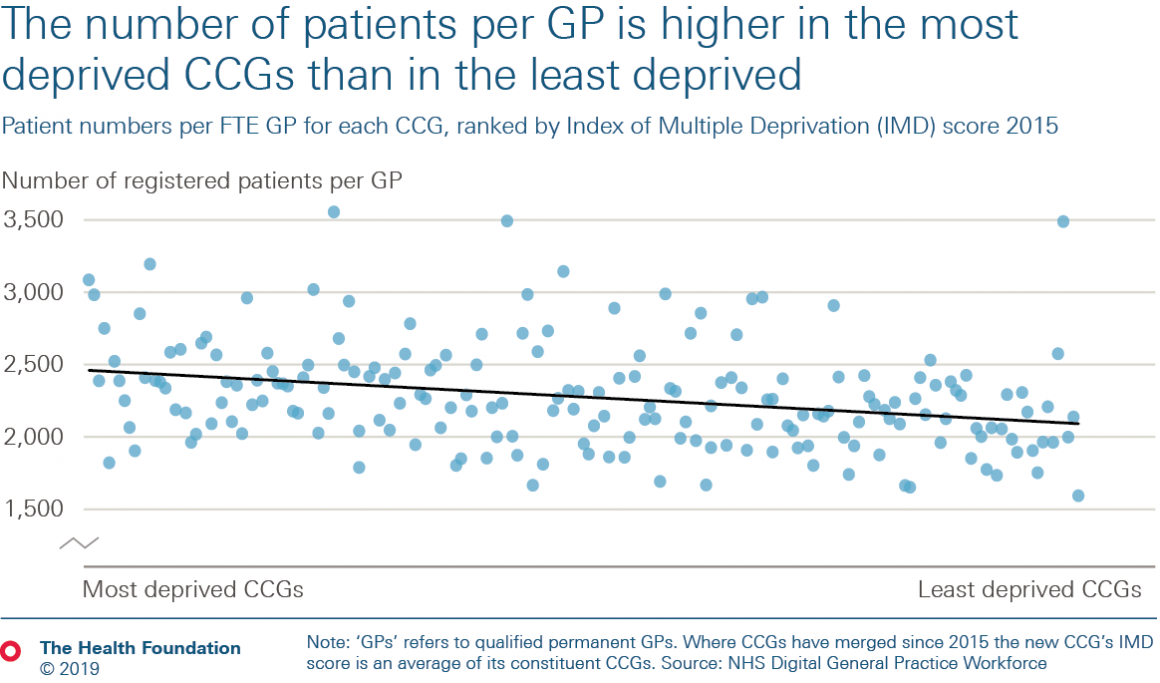

The number of patients per GP also varies by local area – some CCGs have more than twice as many patients per GP as others. That variation isn’t random. The number of patients per GP is 15% higher in the most deprived 10% of CCGs than in the least deprived 10%. That means that on average a GP working in the most deprived 10% can expect to be responsible for 370 more patients than a GP working in the least deprived 10%. There is a lot of variation, meaning that this relationship is not true for every CCG, but the general trend is nonetheless worrying.

Even if all else were equal, more patients per GP means a higher workload for GPs working in deprived communities. But all is not equal and there's a multiplier effect.

People who live in disadvantaged areas tend to experience worse health – they're at greater risk of having multiple health conditions and they are more likely to have multiple conditions at younger ages. Recent Health Foundation research found that around 28% of people in the most deprived fifth of England have 4+ conditions, compared with 16% in the least-deprived fifth. In the least-deprived fifth of areas, people can expect to have 2+ conditions by the time they are 71 years old, but in the most-deprived fifth, people reach the same level of illness a decade earlier, at 61 years of age.

Continuity of GP care has been linked to reduced admissions for conditions which are manageable in primary care and community settings (so called 'ambulatory care sensitive conditions', like COPD and asthma). So reduction in permanent GPs and increasing reliance on locums may make it harder to keep people out of hospital.

And so our vicious cycle becomes a whirlpool.

The number of FTE GPs is falling fastest in most deprived areas, but those are precisely the areas with the greatest health care need. Policymakers hope that increasing the number of allied health professionals working alongside GPs will alleviate some of the pressure. However, we calculate that the number of pharmacists working in general practice is also lower in more deprived areas. On average, there are 8% more patients per FTE pharmacist in the most deprived half of CCGs than in the least deprived half.

Without urgent policy action, GP shortages will get worse.

Our projections, with The King’s Fund and the Nuffield Trust, suggest that if current trends hold, the number of GPs could continue to fall – a further 4% by 2023/24. If this happens, based on current population projections, the number of patients per GP will increase by another 7%. This would mean a total increase of 15% in patients per GP between 2015 and 2023.

So what to do?

NHS England’s targeted enhanced recruitment scheme (in effect a 'golden hello' for doctors training as GPs in hard-to-recruit to areas) has had some success, albeit with relatively small numbers. There are promising signs of increased recruitment in to GP training but keeping early career GPs in the workforce is proving a challenge.

Increasing the number of allied health professionals in primary care – such as physios, pharmacists and paramedics – doesn’t solve the shortage of GPs. It is a pragmatic response though which, if well implemented, may alleviate some workload from GPs. NHS England has promised 20,000 additional allied health professionals by 2023/24, working across new primary care networks (PCNs) but there's no plan to make sure that this workforce will be distributed equitably across the country. Without mechanisms to try to encourage or incentivise recruitment to areas of high deprivation, there's a risk of perpetuating a cycle that could leave PCNs serving the most deprived populations (with the greatest health needs) the least able to recruit.

There's a commitment in the Long Term Plan for the NHS to play a greater role in reducing health inequalities. However, the inverse care law – that the availability of good medical care tends to vary inversely with the need for it in the population served – is alive and well in general practice.

Becks Fisher (@BecksFisher) is a Policy Fellow and Ben Gershlick (@BenGershlick) is a Senior Economics Analyst at the Health Foundation.

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more