This is the fourth blog in a Health Foundation series looking at winter pressures in the health and social care system in 2017/18. In the first blog, Dr Becks Fisher looked at how the NHS is aiming to help us stay well and reduce pressure on hospitals. In the second blog, Tim Gardner explored what is happening at the front door of hospitals. In the third blog, Anna Starling wrote about what’s happening inside hospitals in England. In this fourth blog, Tim Gardner looks at leaving hospital and returning home.

The spotlight on NHS performance during winter – and this series of blogs so far – lingers on problems getting to and (where necessary) into hospital quickly in an emergency. Problems at the hospital front door may seem more immediate, but the less visible delays at the back door are no less important.

Delayed discharges: The impact on older people

Delays leaving hospital primarily affect older people (those aged 65 plus). In March 2017 the NHS Benchmarking Network suggested that 83% of delayed discharges involved people aged 65 plus and 39% involved people aged 85 plus (based on data from 47 NHS organisations from England, Wales and Northern Ireland).

Older adults are at greater risk of ‘deconditioning’ – losing muscle power, strength and abilities due to restricted mobility. A prolonged hospital stay can mean the difference between independence and dependence. It has been shown that for healthy older adults, a 10-day period of bed rest can lead to the equivalent of 10 years of muscle ageing.

It’s imperative to enable patients to leave hospital as soon as they are well enough by providing the support they need to continue their recovery at home and return to their previous routines and activities.

Getting people home frees up beds

Providing the medical and non-medical support to get people home is where NHS community services and social care respectively play an unsung but critical role. Prompt discharges also mean reducing the wait for a bed for the increasing number of people being admitted in an emergency.

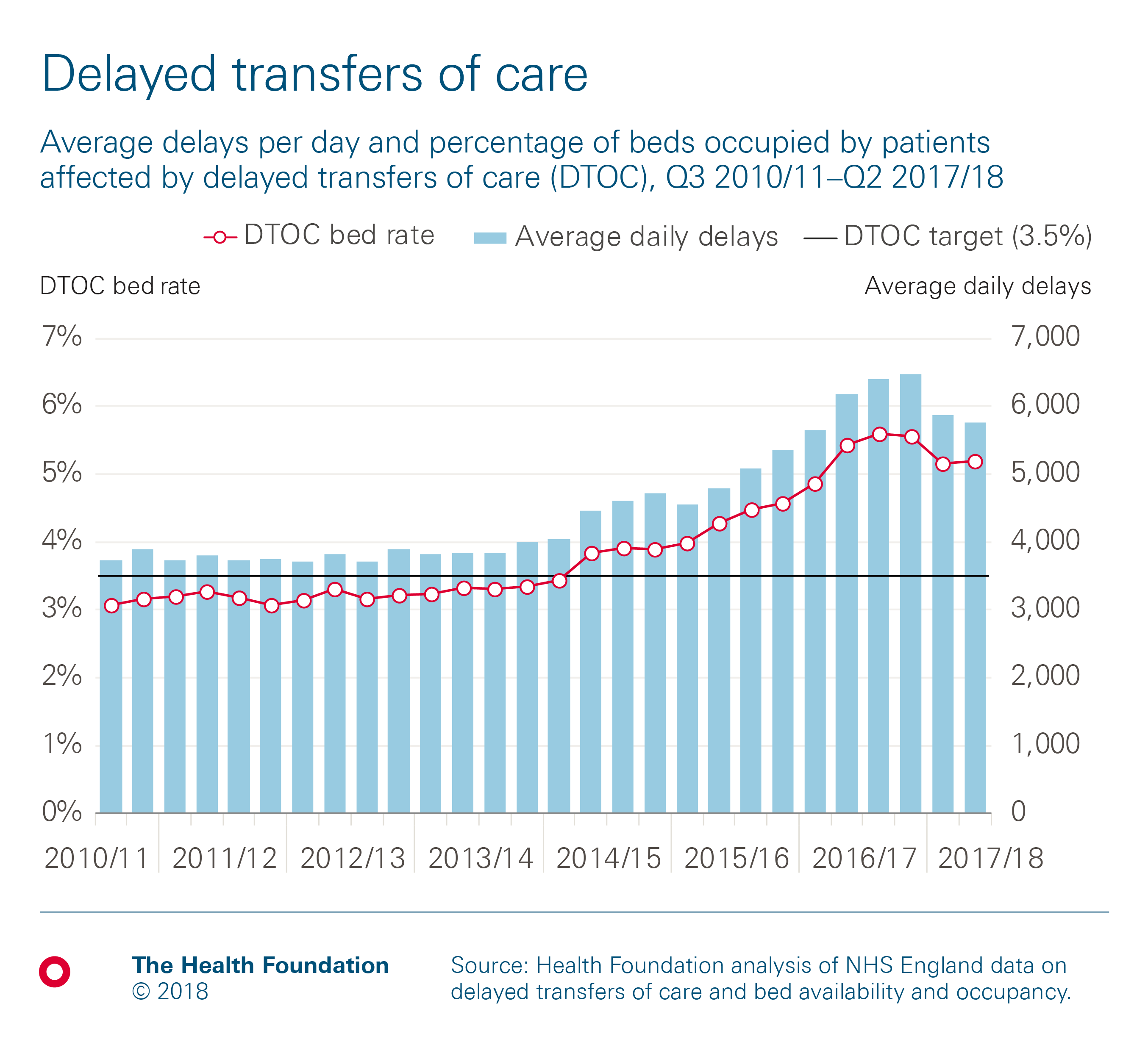

However, delays in discharging patients have become an increasingly big issue over the last few years. Delayed transfers of care amounted to 1.4 million hospital bed days in 2011/12 and increased to 2.3 million days in 2016/17. To put it another way, between April 2016 and March 2017, an average of 6,178 patients per day were stuck in a hospital bed despite being medically fit to be discharged.

The push to reduce delays

The recent growth in delayed transfers sparked a major push in 2017 to substantially reduce delays ahead of winter and free up 2,000–3,000 much-needed hospital beds. This was backed by an extra £1bn of funding for local authority social care services, announced in the Spring Budget.

This push appears to have had some impact. Between April and November 2017, 1.4 million days were lost to delays – around 87,000 fewer than the 1.5 million days in the same period in 2016/17. In November 2017, the latest month for which data has been published, there were 1,271 fewer delays per day than in the same month in 2016.

Reversing the growth in delays is a big achievement, but this is still some way short of the ambitious target set out in the government’s mandate to NHS England. This was to reduce the percentage of hospital bed days occupied by delayed patients to 3.5% (around 4,000 delays per day) by the end of September 2017. This target hasn’t been met, as the following chart demonstrates.

What causes these delays?

NHS England publishes statistics on delayed transfers of care, attributing them either to the NHS, to social care, or often to both (because local authorities can be fined for delays caused by social care).

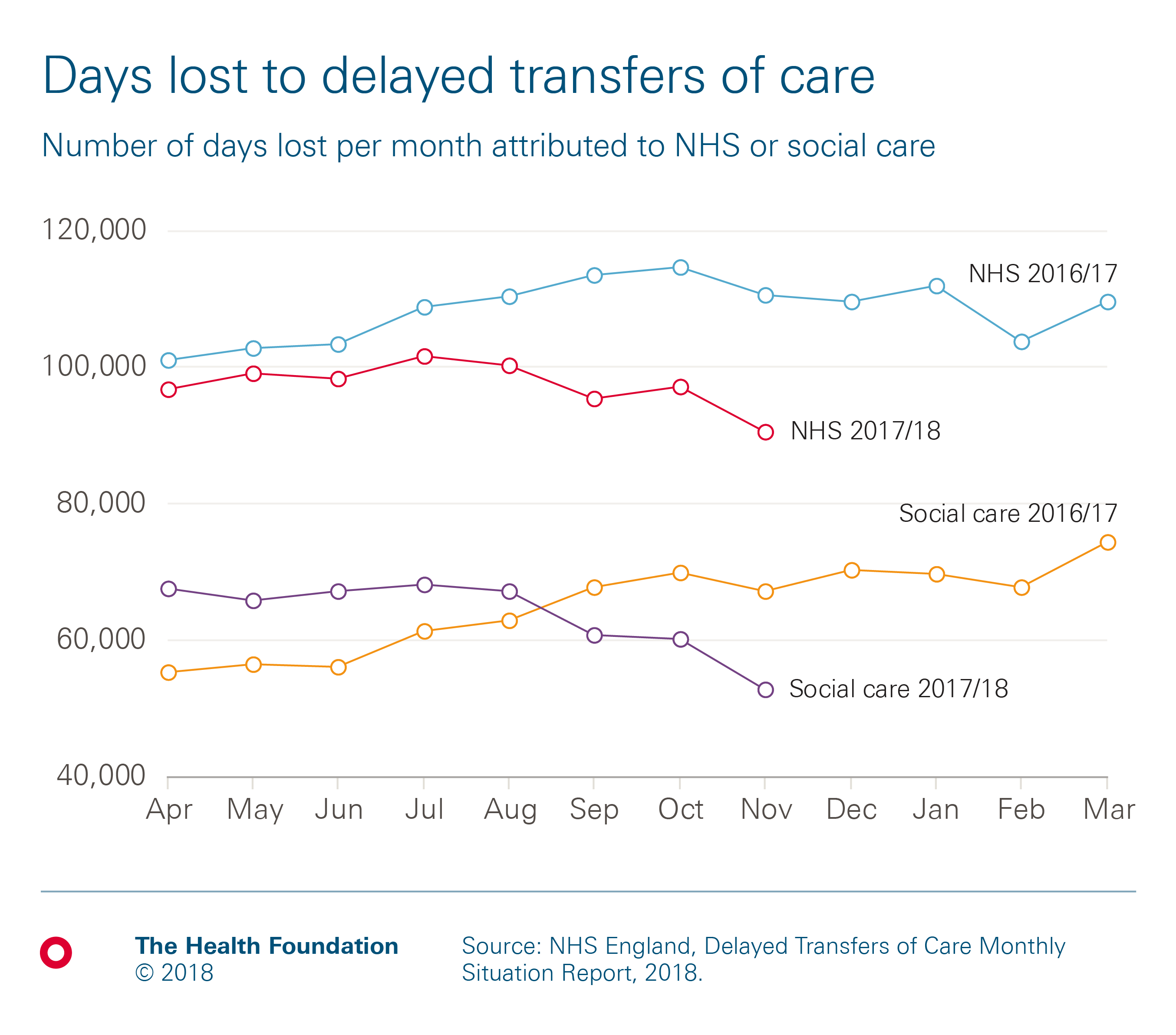

779,039 days lost to delays were attributed to the NHS between April and November 2017, down from 865,121 days in the same period in 2016. These days are likely due to delays arranging district nursing, occupational and physical therapy, and community-based rehabilitation services, which are all increasingly thinly stretched. In contrast, the number of delayed days attributed to social care actually increased from 496,828 in April to November 2016 to 509,477 during the same period in 2017.

The total number of delays doesn’t really do justice to the efforts that local authorities have been making in the context of the precarious state of the adult social care sector. In fact, most of the increase in social care delays occurred between April and August 2017, and the situation improved considerably ahead of winter, as shown by this chart.

The challenge ahead

That progress must be sustained and built upon over the next few months, but the efforts to meet the government’s 3.5% target may have already exhausted the easy gains. The challenge ahead is therefore substantial. While social care increasingly looms large in debates about delayed transfers of care, these services exist to do much more than supporting the NHS by helping facilitate timely discharge from hospital.

A narrow focus on reducing delayed transfers of care can yield results, but the recent Care Quality Commission (CQC) review of six local health and care systems found it risks diverting attention from other important activities. These include preventing people from reaching crisis point in the first place and, given the risks of deconditioning, supporting people to stay well after leaving hospital – both of which are particularly crucial in winter.

Shortfalls in social care capacity

Social care plays a key role in helping people who need assistance with daily living to remain independent and to keep well at home, as do NHS primary and community services. However, there’s a large and growing gap between need and the capacity to meet it – and this is particularly evident in winter.

The CQC review also highlighted shortfalls in care home and domiciliary care capacity, with insufficient investment in the social care workforce. Staff turnover in the adult social care sector reached 27.8% in 2016/17, according to estimates by Skills for Care. The growing problems employers in the sector face in finding, recruiting and retaining suitable people have been fuelled by funding challenges, with a recent analysis estimating a £2.5bn financial gap by 2019/20.

The quality of the social care services actually delivered appears to be broadly holding up. However, CQC estimates suggest 1.2 million people are not receiving the help they need, an increase of 18% on last year.

There are no easy solutions to quickly put social care on stronger foundations to meet the needs of our most vulnerable. Social care was added to the health secretary’s job title just this week, but it has always been part of his department’s policy portfolio. There have been multiple reviews in the last 20 years, but a lack of political will has prevented solutions from being followed through to implementation.

A system under extra pressure

Winter brutally exposes the precarious nature of the gap between need and the capacity to meet it. The NHS is currently weathering a perfect storm of pressures compounded by winter: the community and primary care sectors are weakened, and social care capacity is heavily depleted. As these factors combine, there is an increasing risk that chronic unmet need will increase illness in England. With less capacity to pick up urgent care needs and prevent acute admissions, the whole health and social care system is under even more pressure.

Worryingly, that extra pressure may be enough to tip the balance from a winter that is tough but just about manageable, to one that is unrelentingly grim for patients and staff alike.

Tim Gardner (@TimGardnerTHF) is a Senior Policy Fellow at the Health Foundation

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more