Could we care more? The outlook for social care after the Budget

23 March 2017

Over the course of the last parliament, half a million more people joined the ranks of the self-employed in England, while half a million fewer people received adult social care. In the Spring Budget earlier this month, the first group received a financial blow via an increase in national insurance contributions, while the latter was handed a lifeline.

There was no shortage of outrage over the increase in national insurance contributions and its reversal was swift. But a similar level of outrage has been in short supply over the last decade while cuts have been made to providing care for those in society who need it the most.

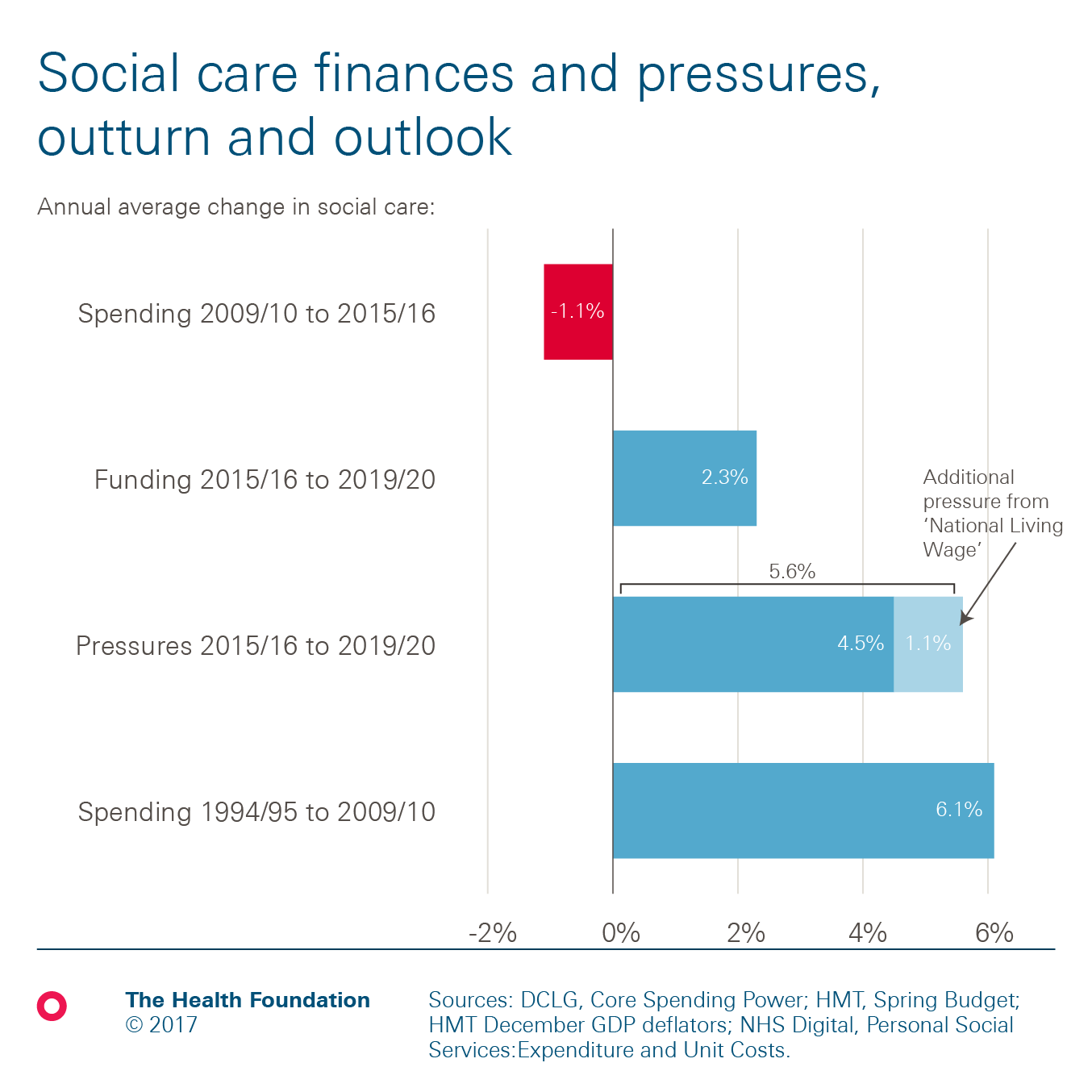

The volte-face on national insurance contributions has been played down by some, with the £2bn that would have been raised over the parliament described as being the size of 'a rounding error' in the context of government spending. This £2bn of revenue (presumably raised for this very purpose) is also the sum total of extra support given to social care: a service that has had to reduce spending by on average 1.1% a year since 2009/10, and which is unable to halt the widening gap between the rich and poor when it comes to receiving care when needed.

In a system that has seen cuts on this level, any new money is welcome. The additional money means that social care will grow rather than shrink between now and the end of the decade (assuming all the new money goes to social care, which is by no means guaranteed).

This growth will be 2.3% on average a year in real terms, which is double the rate of the NHS, an almost unheard of state of affairs.

But even with this new money, we’ll barely be spending more in 2019/20 than we were a decade ago. This is despite demand increasing enormously since then, as the number of people who are older, living with multiple long-term conditions, and coming from other parts of the health and care system rises.

These demographic and systemic pressures will continue. Based on LSE’s model, the pressures on social care are likely to increase by at least 4.5% a year up to 2019/20. In addition there is the impact of the ‘National Living Wage’, as social care is a sector that is reliant on low-paid workers. When the impact of this is added in (on top of expected increases to the pay bill), the pressures rise to 5.6%.

So, if you wanted to provide the same service as there is now you would need to increase funding by at least 4.5% a year on average. This won’t reverse the years of reductions in spending, or give the half a million fewer people receiving care their care back, this will just keep up with the future pressures on the system. And this isn’t a ridiculous amount – it’s still below the trend of 6.1% a year since 1994/5.

And while the new money means spending should increase by 2.3% a year, the pressures of at least 4.5% mean this is only half the rate needed to provide the same service as currently. It is hard to see how the service will not deteriorate as a result. As I’ve said before, health and care is the public finance equivalent of Lewis Carroll’s Red Queen’s race: it has to run as fast as it can to stay in the same place, and run twice as fast to go anywhere at all.

A green paper, due in the summer, aims to put the system on ‘a more secure and sustainable long-term footing’. It will have to find a way of bridging the funding gap between the pressures on the system and the money coming into it, otherwise the welcome relief delivered in the Spring Budget will remain half of what is needed.

Social care was legislated in 1948 in roughly its current form. It was created as a last line of defence against need, and to support those who did not have the means to pay for support. It was the less famous of the post-war national care services, and so it has remained – a brandless but integral cog in a wider system, which you could be forgiven thinking exists merely to support.

Had it been known that the national insurance contributions increase would be reversed, it is unclear whether social care would have received the increase in funding from the Spring Budget. With another attempt at increasing taxes significantly seeming even less possible now than before this episode, local authorities’ focus will return to the tough choices to be made about which services to cut and where care can be delayed or denied. For users of social care and their families, the focus returns to finding ways to pay in order to be cared for. For both groups a real solution can’t come soon enough, but is unlikely to feel much closer.

Ben Gershlick (@BenGershlick) is an Economics Analyst at the Health Foundation

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more