The ‘do nothing’ option: How public spending on social care in England fell by 13% in 5 years

29 May 2018

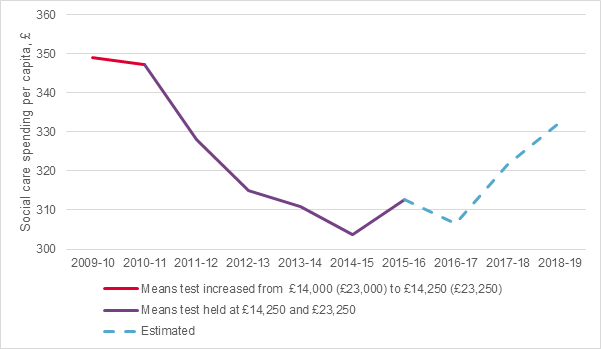

Funding for the adult social care system in England was at its highest point in 2009/10 with total spending of £349 per head of the population in real terms. By 2014/15 it had fallen in real terms to £304, a drop of 13%.

The fall from 2009/2010 to 2015/16 is slightly different at 11%, as 2015/2016 saw the first annual increase of social care funding in six years to £313 per head of the population in real terms. This was, in part, because of the introduction of a £1.9 billion additional transfer to pooled social care budgets from the NHS. Further increases to the social care budget through the Better Care Fund and the social care precept on council tax, led to an increase in real terms to £18.6 billion or £332 per capita.

But how did we, so quickly, get to the low levels of funding experienced in 2014/15? There were no changes made to legislation or eligibility criteria prior to the 2014 care act and demand for social care certainly wasn’t going down. This has all happened at a time when demand pressures for social care are estimated to be growing at around 3.7% per year. So what happened?

First, as our work on public perceptions has shown, it’s risky to assume people fully understand how social care works in England, so here’s our quick guide.

|

How social care funding works in England A person’s eligibility for public funding for adult social care is based on two tests: a needs test and a means test. The needs test assesses people’s ability to perform certain tasks, and the means test assesses their ability to pay for their own care via income, savings or other assets. The means test is set nationally for England. People with assets below £14,250 who meet the needs test are eligible for publicly funded care. People with assets over £23,250 must meet the full cost of their care, until the value of their assets falls below £23,250. People whose assets are worth between £14,250 and £23,250 are expected to contribute £1 a week for every £250 of assets above £14,250. The means test thresholds have a different effect for home care (visits from a social care worker in your own home) and residential care (where you move into a residential or nursing home). For the former you need to have fewer than £14,250 in financial assets (excluding your house), but if you are moving into a residential care home your house is included in the means test. These means test thresholds have been in place since 2010/11, when they were increased from £14,000 and £23,000 the previous year. Since that time, they have been held constant. |

The chart shows how social care funding in England has changed over the last few years. In 2010/11, when the means test was increased, social care funding fell slightly from £349 to £347 per head in 2018/19 money, though increased in total. Then followed a consistent fall in funding from £347 to £304 per head in 2014/15 (£18.3bn to £16.6bn in total).

With increased funding transferred from the NHS, the social care precept and the Better Care Fund, we expect social care funding to grow again, but there have been no changes to the means test.

Source: Spend data for England, Health Foundation analysis of NHS Digital: Personal Social Services: Expenditure and Unit Costs, England

Spend on social care funding fell in part because of the ‘do nothing’ option

One factor in this relative fall in England is a result of something economists call fiscal drag: a serendipitous process in which governments can save money by changing nothing. If things like tax limits or, in this case, means test thresholds, stay constant in the face of inflation then the number of people who are eligible decreases.

For example, if you lived in England in 2014/15 and had assets of £23,040 then you were eligible for government funded care. Say in the next year your assets appreciated by 2%, and at the same time inflation was 2%. Your assets would then be worth £23,500 in nominal terms but in real terms there would be no change. However, you would become ineligible for funded care, without having gained any wealth.

As a result of the government doing nothing, over 400,000 fewer older people accessed publicly funded social care in England in 2013/14 than in 2009/10 – a drop of 26%.

There has been lots of talk in Government of reforming social care (with at least 12 reviews, green and white papers since 1997). But talk of reform that doesn’t gain traction leads to inertia.

The 3.7% annual increase in demand for social care is driven by demographic growth, people living longer with chronic conditions and rising costs. In the face of the fall in funding, if we were to restore access and quality to that last seen in 2009/10 as well as keep pace with the unheeded demand pressures it would require an extra £5bn of spending in 2015/16 and an extra £15bn in 2030/31.

Time to change the ‘no change’ path?

The perceived lack of transparency of how social care is funded and the lack of public education on the subject mean that over the years social care reform as a policy area has not been significantly developed. Steps taken by the Conservative party in its election campaign in 2017 to bring social care to the fore were met with confusion and anxiety.

Other funding systems in the UK that don’t depend so heavily on the means test have not experienced such drastic falls in funding. In Scotland personal care is free at the point of use, and this means that fiscal drag that creates such vast savings cannot go unnoticed.

With more people living long into their golden years, if we want to provide a good level of publicly funded social care it is going to be expensive. The upcoming green paper is another opportunity for the government to deliver reform in England to significantly improve the offer from the state for older and disabled people.

Fiscal drag makes savings to the public purse at the expense of less wealthy social care users. We can either move to a system that relies less on means testing or by improving the means tested system and ensuring that we pick up on fiscal drag. Our recent report, A fork in the road, identified this crossroads and showed that a reformed system could cost no more than ‘muddling along’ with the current flawed system.

We should be alert to the dangers of apathy in a funding system where, as illustrated by fiscal drag, standing still is in fact moving backwards.

Toby Watt is a Senior Economics Analyst at the Health Foundation. Michael Varrow is an independent social care consultant. He recently co-authored the Health Foundation and King's Fund report - A fork in the road.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more