Rethinking access to general practice: it’s not all about supply

Rethinking access to general practice: it’s not all about supply

5 March 2024

Key points

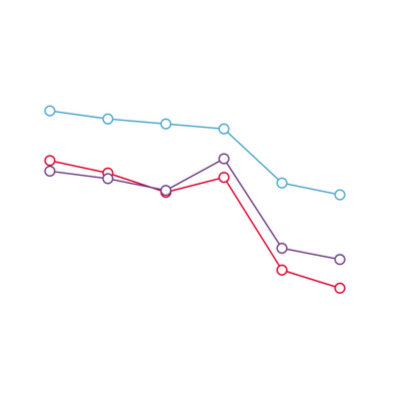

- In recent years, public satisfaction with access to general practice has plummeted. Patients are finding it harder to make appointments, and feeling increasingly dissatisfied with waiting times and the types of appointment offered.

- Despite having fewer GPs in England than there were in 2015, general practice is now delivering record numbers of appointments. A relatively high percentage of these – around 40% – occur on the day they are booked.

- Improving access to general practice has long been a priority for politicians. Numerous policies have attempted to improve access, but have usually focused on the ‘supply’ of appointments: things like how many GPs there are, the number of GP appointments available and how long people wait for them.

- Access to general practice is about more than just the supply of appointments. Broader factors matter too – like how people decide what to do about symptoms, their knowledge of health services and the barriers they face to reach services.

- The ‘candidacy framework’ is a broader way of understanding access by analysing how people identify themselves as ‘candidates’ for health care. Applying this framework specifically to primary care may help policymakers improve access to general practice.

- This long read is the first in a series of outputs from a collaboration between the Health Foundation and researchers at The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute. The project draws on the candidacy framework to inform a more holistic understanding of general practice access issues.

- We set out headline data on access to general practice, describe previous attempts to unlock the access problem, and consider how a broader approach (using the candidacy framework) might drive improvement for patients and practices.

Appendix 1: What’s been tried? A catalogue of efforts to improve access to general practice, 1984 to 2023

The purpose of this resource is to catalogue and categorise attempts to improve access to general practice with a view to informing future improvement efforts. The list includes interventions that have already been tried, are ongoing or have been proposed, and categorises them according to how they are intended to improve access to general practice.

A note on the methods used to create Appendix 1.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more