Improving health by tackling market failure

Improving health by tackling market failure

- This long read explores what market failure is, its relevance for health, and how the government might intervene to improve the population’s health.

- We look at two examples: the success of reducing smoking and how we might use a market failure approach to tackle obesity.

Introduction

What does the government need to do to ‘level up’ across the country? To go beyond a catchy phrase and rhetoric, our nation’s health needs to stay firmly on the government’s policy agenda. Health inequalities are stark – there is a 19.1 year gap in healthy life expectancy at birth across local areas of the UK. It’s a pattern of new relevance to the Conservative party, with 41 of the seats won from Labour in areas with lower than average healthy life expectancy.

There are some promising signs. The Conservative manifesto’s ambition to extend healthy life expectancy by 5 years by 2035 is one, as is the Health Secretary’s stated intention to tackle health inequalities, but it is a very tough challenge, particularly when healthy life expectancy has begun to reverse for women in the last 6 years and life expectancy gains have stalled. Reducing obesity rates and going ‘smoke free’ look to be key government aims to improve health, but the policy prescriptions are less certain.

It is widely accepted that the state needs to play a major role in ensuring high-quality health care is available to everyone, and – as the coronavirus outbreak demonstrates – control infectious disease. But beyond tackling acute health need there is far less consensus around the state’s role in keeping us healthy in the first place. On issues such as smoking and obesity what’s needed are more upstream, preventative policies that maintain health. However, concerns about the perceived unpopularity of these interventions, which can be seen as limiting individual freedoms or unnecessary state interference, tend to stifle the long-term change that’s needed.

Nevertheless, there is a long history of the state taking responsibility for people’s health –from Victorian sanitation systems to vaccination programmes and tobacco control – in ways that are now simply accepted by society. Concerns about state overreach in measures to maintain good health can start to be addressed by taking a market failure approach. This means applying the economic framework used by civil servants to determine when policy change is needed.

This long read explores what market failure is, its relevance for health, and how the government might intervene to improve the population’s health. We look at two examples: the success of reducing smoking and how we might use a market failure approach to tackle obesity.

What is market failure?

In economics, ‘market failure’ is a situation in which market forces lead to a reduction in societal welfare. Take, for example, pollution created by a manufacturer, where the harmful impact on society is not paid for by the manufacturer. If there is no mechanism to force the manufacturer to pay, there is little incentive for them to limit or change their polluting activities. Within market economies such as ours, addressing market failure is a key rationale for government intervention.

Over time, views on which outcomes are the result of poor market functioning change for two key reasons. First, understanding reasons for market failure improves with time. Second, notions of societal welfare are subjective and evolve. Identifying and acting on market failures depends as much on current public attitudes and values as it does on existing evidence.

There are four broad categories of market failure recognised by HM Treasury’s The Green Book (see Box 1). These are the under-provision of public goods, imperfect information, positive or negative externalities and market power.

Under-provision of public goods or services: Where goods or services that benefit the whole of society are under-provided by markets – first, because it is difficult to stop others from using or benefiting from them and, second, because the quantity needed tends not to vary by how many people require them. Examples include defence and street lighting.

Imperfect information about goods and services: The buyer and seller have different information about a good or service, leading to:

- adverse selection – for example, a second-hand car sale where a buyer may be unaware of the true condition of the car

- moral hazard – for example, when a person’s behaviour alters after the risk of their actions is borne by others – such as being less careful about belongings after taking out insurance.

Externalities: Where consuming a good or service affects others – either positively or negatively. One example is passive smoking, where inhaling second-hand smoke has a negative impact on health of others. Another is pollution, where the production of a good pollutes an area. ‘Merit goods’ are goods and services that are often subsidised by governments because of a recognition of their positive externalities – they benefit society not just the individual, such as education or health care.

Market power: A lack of competition renders a market inefficient. For instance, a firm with monopoly power can dictate price levels of the goods or service that only they can provide. This type of power usually stems from an ability to restrict access to a given market, such as geographical location, high entry costs, or practices such as ‘predatory pricing’ to undercut competitors in the short term.

Market failure and health

One prominent example of a health issue bearing substantial cost to society and reducing social welfare is obesity. Latest data show that one third (34.3%) of children aged 10–11 in England are overweight or obese, and almost two thirds (64%) of adults in England are overweight or obese. This increases their likelihood of developing various conditions including heart disease, stroke, diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders, depression, and cancer, with societal costs conservatively estimated to be as much as £27bn. There are long-term consequences, too: obese children are more likely to go on to become obese adults, with all the inherent risks that this entails.

The costs and harms of obesity are not fully taken into account by the market. Food companies set their price in relation to their cost of production and sourcing ingredients, not the subsequent implications for population health – these are negative externalities. Consumers are often unaware of, or don’t consider, the longer term health consequences of the food and drink they consume meaning that there is imperfect information leading to adverse selection.

So, what can be done to address these market failures? The next section explores the key policy levers available to governments to improve health.

How can the UK government intervene to improve health?

There are wide range of factors that influence our health such as where we live, where we work, access to food and access to health services. Given this, there are also a broad range of potential market failures that could be addressed. The question is, then, how should the state intervene to correct market failure?

Government can try to correct market failure through four main channels: taxation, regulation, public spending, and information (see Box 2). In the UK, these tend to be delivered by central government and, to a lesser degree, through local government.

Taxation: Taxes are well known to influence the behaviour of companies and individuals through their effect on the prices of targeted goods and services. Some taxes are designed specifically to reduce the quantity of a product consumed (such as the high rate of tax imposed on tobacco products) or the nature of products (the soft drinks industry levy). Taxes also play an important redistributive role.

Regulation: Controlling the supply of particular goods, services or activities has proved highly effective for tackling public health issues – especially on a national scale. The 2007 ban on smoking in public places is a prime health-related example. Other important applications of regulation to improve health include road safety measures, employment and workplace standards, and licensing of gambling and alcohol sales.

Spending: This takes two main forms, both of which can be redistributive:

- direct transfers – for example to people (eg through social security payments) or firms (eg subsidy payments). From a health perspective, this can be important in increasing resources for low income families

- directly funded service provision or investment in infrastructure – for example provision including universal education or health care, or funding to local authorities.

Information: The provision of information can help people, businesses and other institutions to make more informed choices about the activities they engage in, or the goods they consume. However, it is important to understand the constrained choices people may face when seeking to influence their behaviours, irrespective of their level of knowledge.

Policy success often involves pulling a combination of these levers. This is particularly the case when aiming to improve an outcome such as health, where the factors at play are complex and interrelated.

Government successes in improving health

Successful public health policies that aim to address market failures require both identifying the relevant market failures at work and achieving public and political consensus for lasting change.

Some of the biggest health policy successes of the last 2 centuries are now accepted aspects of our lives. For example, the UK’s public sewer networks were built in the 1850s and 1860s to cope with the consequences of urbanisation following rapid industrialisation. Today, these are largely taken for granted, but are a public good with clear health benefits.

Another example is immunisation against diseases such as smallpox and polio leading to their eradication, or near eradication. These ‘merit goods’ – subsidised by government and of benefit to others beyond the individual treated – have resulted in rapid improvements in population health.

Efforts to reduce smoking, which have been ongoing since the 1960s, provide some classic examples of addressing market failure.

Tackling smoking

For decades, smoking has been the leading cause of death and illness in the UK and the biggest contributor to the gap in life expectancy between the most and least deprived parts of society. In the tobacco industry, there are multiple market failures at work. The extent and forms of policy intervention used to combat these have grown gradually over time as public perceptions have shifted against tobacco products.

Perhaps the most obvious market failure is the negative externalities borne by the individual, and those around them, when they smoke. The cost price of a cigarette fails to take into account the cost of poor health to the individual, the addictive nature of the product and the potential harm to others through passive smoking. These all have significant societal costs through health treatment and lost productivity.

There are also important information asymmetries. People are unlikely to understand the addictive nature of tobacco when they first smoke. Nor are the evidence-based health implications immediately obvious – even if people are broadly aware of links between smoking and cancer. Additionally, people tend to prioritise immediate gratification over likely negative long-term consequences.

The other aspects to information asymmetry are the roles of advertising, the media and societal norms in shaping and enabling the choices individuals make. For most of the 20th century, smoking was promoted as a positive choice in adverts widespread through sport and media. Film stars often smoked, and in certain places – from workplaces to restaurants and more recently pubs and betting shops – smoking was an accepted norm.

Government intervention on smoking

Experts were aware of the health risks of smoking in the 1950s. However, thanks to the popularity of smoking, its addictive nature, and support from a powerful industry protecting its own interests, government action on smoking was slow.

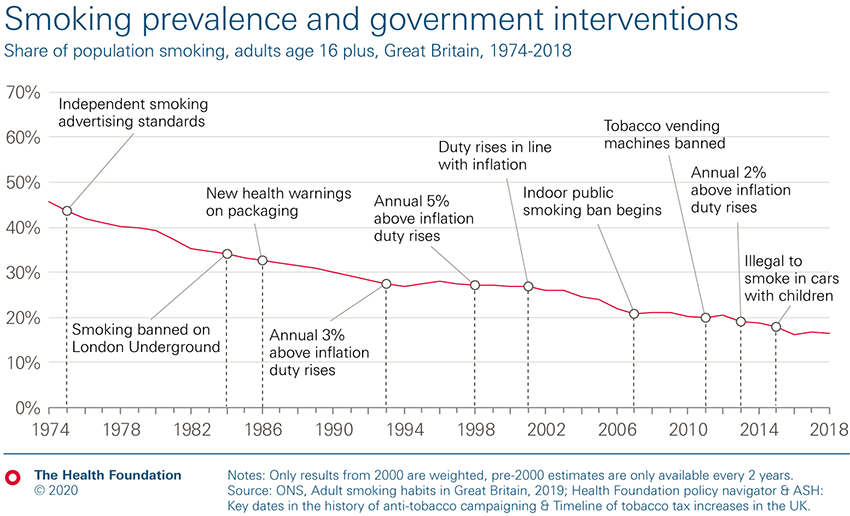

It was not until the 1960s that significant policy interventions began to be introduced (see Figure 1). With increasing evidence of its impact on individuals and society – alongside changing public attitudes – the number and reach of policies addressing smoking-related market failures increased over time. The most recent legislation in 2015 saw the ban of smoking in cars with children (see Figure 1).

As the government began to take action, smoking rates have fallen since the 1970s, declining from 46% in 1974, to 17% in 2018.

Figure 1:

Three key policy levers have been used to reduce smoking rates, each one specific to the market failure they are trying to address:

- Taxation has been used to address the problem of negative externalities not taken into account in the consumer price. Additional duty on tobacco products has been increased to the extent that just over two-thirds of the cost of a £10 pack of 20 cigarettes is tax. This ensures that the price the consumer pays more closely reflects the individual and societal costs of smoking.

- Information and education campaigns have been used to address information asymmetry, publicising the harmful effects of smoking and passive smoking.

- Regulation has been used to place limitations on where cigarettes are sold, consumed, and advertised, as well as addressing information asymmetry by ensuring that products carry a clear health warning.

Taken together, these policies have not simply attempted to change the smoking patterns of current smokers, they have helped to reduce the flow of new smokers, nudging people away from starting smoking in the first place. They have done this by making it more difficult, more expensive, and less socially acceptable to smoke. The whole environment that supported smoking has now changed, with stronger and more far-reaching government interventions being introduced as public attitudes against tobacco use have grown. The negative externalities created by smoking are also far better understood and policy has shifted accordingly.

What next?

In recent years, smoking rates – while at a historic low – have been harder to shift. Prior to the election the government announced a smoke-free 2030 ambition. However, it is unclear how it will achieve this, and any policy approach has trade-offs.

From a historical perspective the obvious next step might appear to be further regulation including smoking prohibition. As with the introduction of previous regulatory measures, this would raise fears that the costs of stopping illegal tobacco sales would rise, although there is little evidence that has been the case following the restrictive measures put in place to date. Perhaps, more importantly for government, it would likely lead to protestations of restricting individual choice, and it is unclear whether public opinion would support further restrictions.

A more likely policy route is further tobacco duty rises, to raise prices and reduce demand. However, smoking is far more common among more deprived communities with those who still smoke likely to either find it hardest to stop or continue despite knowing health risks. Therefore, the immediate impact of tax rises is likely to be regressive. In 2016, in England’s most deprived 10% of local areas, 27% of adults were smokers. In comparison, in England’s least deprived 10% of local areas, the figure was just 8%. So, paying a higher price will squeeze the budgets of the poorest households.

Yet the long-term health gains could be significantly progressive – greater health benefits among more deprived populations. The rate of avoidable deaths from respiratory disease is far greater in the most deprived local areas.

Because of the addictive nature of tobacco, in the face of higher prices consumers may purchase cigarettes on the black market or may prioritise tobacco over other household goods. Both situations would require further state action in the form of more enforcement and better access to smoking cessation services. Yet funding for smoking cessation services is estimated to have fallen by 45% in real terms between 2014/15 and 2019/20. This is largely a consequence of year-on-year real term reductions of the public health grant.

Smoking policy is a classic example of government interventions designed to address market failures, and how societal, market and political environments initially tempered the policy response. A renewed focus on reducing smoking rates is important to help improve and maintain the population’s health. Further policy action should include a continued mix of approaches (taxation, information and regulation), as well as appropriate funding for stop smoking services, which could help alleviate short-term regressive impacts. The next section considers how these lessons can be applied to help tackle obesity.

How could we use market failure to address obesity?

Given the lessons of tackling tobacco use, how might the UK government do more to address obesity?

Obesity is a far more complex and multifaceted problem than smoking. As such, it will require a multifaceted solution: obesity rates are unlikely to be reduced through one single policy measure. Obesity is a product of a wide range of determinants of our health, including our socioeconomic group, social norms, the availability and affordability of healthy food, opportunities for physical activity, transport infrastructure and the information we are exposed to. And unlike the tobacco industry, having a strong food industry to feed the population is a national strategic priority.

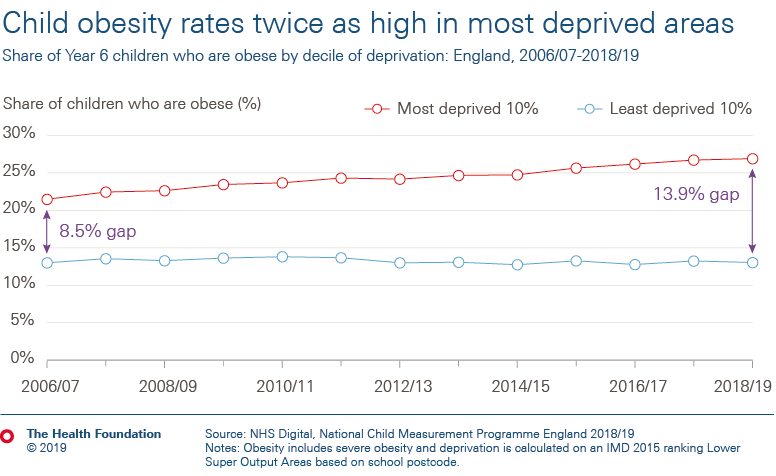

There is also a problem of fairness. As a child you have a higher chance of being obese if you are from a socioeconomically-deprived family or community. The growing rate of obesity among children from the most deprived areas is driving an overall increase in obesity rates for children aged 10–11.

Figure 2:

Information and constrained choice

Interventions are often targeted at those who are already obese and at high risk of developing a health condition. So, they are largely health care related ‘merit goods or services’, reflecting the public consensus that poor health should be treated free at the point of use. One example is bariatric surgery for obese adults, which can be a highly cost-effective procedure recommended by NICE for specific patient groups. Another is the recently announced NHS trial of very low-calorie diets for patients who are both overweight and have diabetes.

Information provision is also a popular tool. An individual approach gaining political popularity is personalised prevention. This seeks to address information asymmetry by telling patients about the longer term implications of their genetic risk of disease or their likely individual consequence of unhealthy actions. Unfortunately, evidence published in The BMJ and the Annals of Behavioral Medicine so far suggests that this approach has limited impact. This may reflect the human tendency to prioritise short-term reward over long-term health consequences, and the fact that wider living conditions that reinforce unhealthy actions remain unchanged.

At the population level, interventions have tended to prioritise information campaigns as a means of tackling information asymmetry. A current example is the government’s social marketing campaign Change4Life. This mass-media campaign informs people how to eat more healthily, stay physically active and maintain a healthy weight.

The impact of such campaigns is likely to be limited in part because public education campaigns have to compete with market power. They are in direct competition with food industry campaigns and supermarket or restaurant pricing strategies that seek to maximise profit rather than societal benefit, often encouraging more consumption of unhealthy food rather than less. Similarly, front-of-pack nutrition labelling and calorie labelling in restaurants may also have some benefit – indeed, both are proposed in the government’s recent prevention green paper. But their impact is likely to be limited by standing in direct competition with enticing offers encouraging over-consumption that can appear alongside the same products.

Engaging with the advice of education campaigns such as Change4Life also requires high levels of individual agency. You have to see a food-related Change4Life advert, engage with it, absorb the information and then act on it. At each step, it is likely that some people will not proceed to the next stage, with only the most motivated subsequently changing their behaviour. This could widen health inequalities as engaging with high-agency interventions is often easier when you are more educated, have more money, and more time – all factors that are socioeconomically patterned.

There are few examples of direct interventions to prohibit the supply of food stuffs unless they pose an acute risk to health, such as through disease transmission. Although the strict control of trans fats in Denmark is one such example.

Taxation – a tool to tackle obesity?

Another policy tackling an obesity-related market failure was the introduction of the UK Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL). This seeks to reduce the amount of sugar, and therefore calories, in soft drinks. Public Health England estimated that between 2015 and 2018, the levy has led to an average 29% reduction in the sugar concentration of soft drinks and a commensurate 20% fall in the average number of calories from each drink.

As with tobacco, one of the principal arguments against taxes on products such as soft drinks is their regressive nature – lower-income households consume more of the products and they represent a greater share of these families’ income. However, the levy aimed to change manufacturer behaviour rather than raise prices. This was achieved by the levy having three tiers dependent on a drink’s sugar content:

- a higher tax rate of 24p per litre for drinks with high sugar concentrations (more than 8g sugar per 100ml)

- a lower rate of 18p per litre for drinks with between 5g and 8g sugar per 100ml

- no tax at all for drinks with less than 5g per 100ml.

Early data from the SDIL’s evaluation suggest that the tax is having its intended effect: manufacturers have dramatically reformulated their products into lower-sugar alternatives, and while people appear to be buying at least as many soft drinks as before they are being exposed to less sugar. All other things being equal, this should ultimately improve health.

There are potential trade-offs for the government in legislating to affect prices or choice. They can be unpopular, have an impact on people beyond the target population and can rub against industry profit motives. However, despite a negative response from industry, public support for the levy remains strong.

In time, it is possible that people will choose to switch back to higher-sugar alternatives, or that manufacturers will pass more of the cost of the levy on to consumers by increasing prices. This will become clearer as more results from the levy’s evaluation are published but to date it appears to be working. So, what next?

One reason for a greater focus on interventions such as the SDIL is that efforts to encourage industry to voluntarily engage with public health measures have sometimes proven unsuccessful. The Food Standard Agency’s voluntary approach to salt reformulation led to an 11% reduction in salt intake between 2003 and 2011. However, the equivalent sugar reduction programme (aiming for a 20% fall in the average amount of sugar in targeted foods sold by retailers and manufacturers by 2020) led to a decline of only 3% between 2015 and 2018.

It isn’t surprising that there are calls to extend the SDIL further to other foods that can be unhealthy when consumed in quantity, such as confectionery. A recent study has suggested a 20% tax on confectionery, biscuits, and cakes could reduce obesity rates in the UK by nearly 3%: a huge amount for a single policy.

However, food taxes – and, in particular, taxes on specific nutrients such as sugar – are different to the SDIL. The number of different foods that people may switch to is far greater and more difficult to predict for a food tax than the alternative drinks people might choose for a soft drink tax. And those substitutes are not automatically healthier, for example, people may switch from a food high in sugar to another that is high in salt or unhealthy fats. Additionally, from a practical point of view, it is easier to reformulate some foods than others without consumers noticing, or without undermining the integrity of the product.

Changing the food environment

The challenges set out point to the need to move beyond changing individual products to instead changing the food environment. A range of approaches have been advocated, including:

- ending the sale of energy drinks to children under the age of 16

- calorie labelling in restaurants, cafes and takeaways

- banning promotions on food and drink high in fat, sugar and salt

- introducing a 9pm watershed for TV advertising of products high in fat, sugar and salt.

While such policies may individually have small effects on people’s diets, together they may help start to reverse the worrying trends in childhood obesity and to reduce adult obesity.

Discussion

So, how can the lens of market failures help in developing public health policies?

Obesity and smoking are often seen as issues driven by individual behaviours. Yet these behaviours are shaped by the conditions in which we live day to day; they are systems issues. Government needs to recognise that public health challenges such as obesity and smoking are a result of multiple market failures, including:

- a lack of understanding and recognition of negative externalities created by the food environment

- insufficient funding of ‘merit goods’ such as smoking-cessation services, which would have positive externalities beyond helping the individual

- conflicting information, both to encourage and to discourage, consumption of certain products

Considering public health risks through the economic framework of market failure can help to better identify and justify appropriate future policy interventions. It can also help with debates about the appropriate role of government in improving health. Addressing market failures should not be seen as limiting individual choice, but as helping to provide equal opportunity for, and access to, healthier options.

Government approaches to public health often lack the cross-departmental coordination needed to address complex societal health issues. But by using the right mix of taxation, regulation, financial and practical support, and information provision across departments, the government has the power to create environments that encourage and maintain good health.

A sense of urgency to address the long-term impact of current threats to people’s health is missing. If the government meets its aim for a smoke-free society by 2030, it will have taken around 70 years of continued policy intervention to eradicate smoking – despite decades of clear and compelling evidence of the consequences for individuals and society as a whole. Reversing trends in obesity is an even more complex problem to tackle than tobacco, but if it takes as long as 70 years to tackle, there will be profound consequences for people’s health, the health care system, and wider society.

Garnering political and public support to make lasting change may not be straightforward. There is a need to make a clear, evidence-based case for government action and to forge a cross-party consensus to support it. It will also be important to engage with local communities experiencing poor health to understand how to shape interventions, making them as effective as possible within those local contexts.

Finally, it is important to remember that although childhood obesity and smoking are top of the government’s public health priority list, they are not the only areas in need of attention. Air pollution, alcohol and drug misuse, and climate breakdown all pose significant threats to the future wellbeing of the UK population. If the government has the confidence to learn the lessons of the past, and explicitly apply the framework of market failures to public health challenges, it may be possible to fast-track the creation of a healthier population.

Further reading

Share this page:

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more