Comparing G7 countries: are excess deaths an objective measure of pandemic performance?

10 June 2021

Key points

- Rankings are satisfying and, at their best, help us to compare performance – understanding who is best, who is worst and, most importantly, why. However, these comparisons are also fraught with risks. Countries vary, and simply changing your outcome measure can radically alter who performed ‘best’ or ‘worst’. To some extent, we can make league tables say what we want them to say.

- Excess deaths are generally agreed to be one of the fairest ways of comparing the impact of the pandemic on mortality. However, even here, tweaks to our measurement can change our conclusions, though not our overall rankings.

- Our first measure compares the wealthy countries of the G7, across the period March 2020 to February 2021, looking at excess deaths as a proportion of the expected number of annual deaths. Using this measure, the US is the worst performer. They have around 25% more deaths than would be expected. The US is followed by the UK, Italy, France and Canada. Germany and Japan have fared best.

- For this comparison we base our ‘expected’ deaths on the average of deaths in the years 2015–19. But in this time period the US, Canada and Japan have had rapidly rising deaths. Taking an average does not take account of this rising mortality, and therefore leads us to overestimate excess deaths.

- When we calculate excess deaths based on trends in deaths, rather than just averages, the US’s comparative performance ‘improves’, and Japan moves to having ‘negative’ excess deaths – fewer deaths than would be expected. The overall ranking, with the US and UK being the worst performers, remains the same.

Introduction

League tables are popular. Rankings are satisfying and, at their best, help us to compare performance – understanding who is best, who is worst and, most importantly, why. COVID-19 comparisons are no different and, as we emerge from pandemic and the Prime Minister prepares to host the G7 summit this weekend, academics, politicians and journalists are increasingly comparing how countries have fared.

A common way to do this is to look at excess deaths during the pandemic. This takes all the deaths that occurred during the pandemic (not just those identified as being due to COVID-19), and compares this figure to what might be expected, based on previous years. This allows us to account for differences in identifying and reporting on COVID-19 in certain countries – for example because they did less testing, or because they define COVID-19 deaths differently. It also takes account of indirect deaths from COVID-19, such as those that occurred because people delayed accessing care for other conditions.

As the first wave of the pandemic came to an end in summer 2020, we worked with the BBC on a comparison of excess deaths across selected wealthy countries. Since then there has been a second wave of COVID-19, but deaths in the countries we analysed are now relatively low again, and vaccination programmes are generally well underway. Now is therefore a good time to update the comparison – and to examine some of the key limitations with this method.

Excess deaths in the G7

In this analysis, we compare the G7 countries (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK and the US) using excess deaths as a percentage of expected deaths in 2020. We calculate ‘expected’ deaths by taking the average annual deaths between 2015 and 2019. Excess deaths is the number of actual deaths, less the number of expected deaths. So, if a country had an average of 100,000 deaths each year (2015–2019), and 120,000 deaths in 2020, we would conclude that they had 20,000 excess deaths in 2020.

Figure 1 shows this measure, for each week of the pandemic, for all G7 countries.

It shows that, in the first wave, the UK had the highest peak – but the UK’s second wave peaks were similar to those seen in the US and Italy. Between the first and the second wave, excess deaths in the US remained at much higher levels than in other countries.

The timing of wave peaks is also interesting – we may all remember that Italy was the first European country to be hit by the pandemic, but it might seem surprising that both Italy’s and France’s second waves hit before the UK’s, given that the B.1.1.7 variant (now known as the Alpha variant) originated in the UK.

Figure 1

The table below shows actual, expected and excess deaths in the G7 countries during the 12 months to February 2021. This gives us a sense of the total impact of the pandemic, showing that the US has been hardest hit, followed by the UK, and then Italy. Japan and Germany were the least affected countries during this period.

| Country | Deaths | Expected deaths (5-year average deaths) | Excess deaths | Excess deaths as a share of expected deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | 3,566,645 | 2,845,479 | 721,166 | 25.3% |

| UK | 735,854 | 613,484 | 122,370 | 19.9% |

| Italy | 766,561 | 657,417 | 109,144 | 16.6% |

| France | 679,538 | 601,380 | 78,158 | 13.0% |

| Canada* | 312,700 | 280,174 | 32,526 | 11.6% |

| Germany** | 1,025,105 | 949,820 | 75,285 | 7.9% |

| Japan | 1,392,889 | 1,337,896 | 54,993 | 4.1% |

Source: Our World in Data based on the Human Mortality Database and World Mortality Dataset

*Canada’s excess deaths are only counted to mid-February 2021.

**Germany’s expected deaths are average of 4 years, 2016–2019.

An objective measure?

The number of excess deaths is often considered an objective measure. Deaths are clearly defined and usually well-recorded, and are not significantly affected by subjective judgement (such as what caused the death), or other factors like testing rates. But, to calculate excess deaths we also need to calculate an estimate of ‘expected’ deaths. This can either be based on an average from previous years (we have used 2015–19 here), or modelled, where additional factors can be taken into account, such as population structure or longer term changes in mortality.

Averages are used by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) in its calculations for England and Wales – and by us in this and previous articles. But this approach, while simple, has limitations – particularly when comparing countries where mortality is flat, with those where it is falling or rising.

Figure 2 illustrates this challenge. It shows deaths for each G7 country over the years 2015–19, with the earliest year – 2015 (2016 for Germany) – indexed to 100. The numbers of deaths in Canada and Japan have grown sharply (almost 8% over the period), reflecting the population structures in these countries. This means that the average number of deaths in these countries (over 2015–19) is lower than the number we would actually expect in 2020, making excess death figures based on averages considerable over-estimates. The average and the number actually expected (based on continuation of the 2015–19 trend) are shown on the chart.

Figure 2

One way to deal with this problem is to calculate the ‘expected’ number of deaths based on the trend – rather than the simple average.

Take the US for example. The number of deaths has increased by 5.6% – an average annual rate of around 1.4%. Basing our expected number of deaths on the 2015–19 average does not take into account this annual growth. If we did take this into account, the expected number of 2020 deaths would rise from 2.85m to 2.96m. In turn, this would reduce our estimate of the number of excess deaths, from 710,000 to around 600,000. And the excess deaths as a share of the expected deaths would reduce from 25.3% to 20.2% – about the same level as the UK.

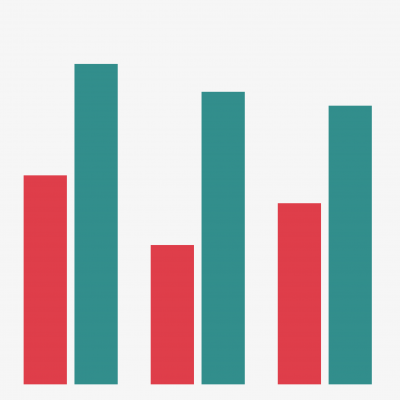

Figure 3 compares these two methods – one based on the 5-year average, one based on the trend. The ranking of countries remains the same but, using the trend, excess deaths in the US decrease substantially, and are much closer to the UK’s. Germany and Canada also move much closer together. The gap between Italy and France widens – Italy’s excess deaths are actually higher using this method. Japan is shown to have negative excess deaths – fewer people died in 2020/21 than would be expected, given historic trends.

A more sophisticated version of our trends approach is taken in a recent paper which compares 94 countries worldwide, using the same metric of excess deaths as a share of an annual baseline mortality. This produces the same overall ranking of G7 countries.

Figure 3

Conclusion

Excess deaths, expressed as a share of expected deaths – is a relatively robust way of comparing countries’ performance during the COVID-19 pandemic – and comparisons consistently show that, of the G7 countries, the US and the UK have fared the worst, and Germany and Japan the best.

But, as with all measures, we need to construct and calculate it with care. Calculating ‘expected’ deaths based on 5-year averages might seem intuitive and simple, but actually biases against countries – including four of the G7 – where the numbers of deaths have been rising year-on-year. When we calculate excess deaths based on trends in deaths – rather than just averages – we see that the US’ comparative performance ‘improves’, and Japan moves to having ‘negative’ excess deaths, fewer deaths than would be expected.

Across the world, COVID-19 has taken the lives of millions of people and left many more friends and families bereaved. As vaccination helps us emerge from the pandemic, and the G7 meet to discuss global recovery, we need to ensure that we learn the lessons. Cross-country comparisons will be an important part of this learning, but they need to be grounded in fair comparisons, not political expediency. This means comparing similar sets of countries, using measures which are objective and robust.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more