Elective care: how has COVID-19 affected the waiting list?

27 September 2021

Key points

- This analysis looks at what we know about the waiting list for elective care in England.

- While the NHS delivered a remarkable amount of elective treatment during the pandemic, the pressure of caring for large numbers of patients seriously unwell with COVID-19 has led to the waiting list for elective care reaching the highest level since current records began.

- Data show that 6 million fewer people completed elective care pathways between January 2020 and July 2021 than would have been expected based on pre-pandemic numbers.

- Services in every part of England were placed under enormous strain during the pandemic, but the backlog in elective care is not evenly distributed. Elective care has been hit harder – and recovered more slowly – in certain parts of the country.

- Just as COVID-19 has exacerbated existing inequalities in other parts of life, access to elective treatment fell further in the most socioeconomically deprived areas of England between January 2020 and July 2021 than in less deprived areas.

- As well as fewer patients being treated, 7.5 million fewer people were referred into consultant-led elective care between January 2020 and July 2021 than would have been expected based on pre-pandemic numbers. These 'missing patients' remain the biggest unknown in planning to address the backlog of unmet need created by the pandemic.

Introduction

Earlier this year, we looked at the stark impact of the pandemic on elective care in England. The initial outbreak of the virus forced the NHS to postpone enormous volumes of planned treatment, such as non-urgent operations, to free up staff and beds for patients seriously unwell with COVID-19. This had consequences for the millions of people who use routine hospital services every year.

Thanks to the hard work of NHS staff, considerable progress was made in restarting services before last winter. While the second wave of the virus then put the health service under extreme strain, far less elective care had to be suspended than during the previous wave. And in March 2021 the NHS unveiled a new COVID-19 recovery plan, backed by £1bn extra funding and a programme to support innovation.

COVID-19 is still putting additional pressure on the NHS. While the vaccination programme has definitely weakened the link between case numbers, severe illness and hospital admissions, the number of patients in hospital with the virus has steadily increased in recent months.

However, COVID-19 is not the only extra factor burdening the NHS now. Delays, disruption and backlogs in health and social care services have started to manifest as the wider impact of the pandemic becomes clear. And the NHS was struggling to manage with relatively low levels of hospital capacity even before COVID-19 struck.

What are the consequences of these pressures for patients waiting for much-needed routine hospital services? Has activity in elective care been fully restored since the second wave of the pandemic? And has that recovery happened consistently across the country?

Here we present six charts looking at the impact of the pandemic on consultant-led elective care, using monthly referral to treatment waiting time data published by NHS England.

COVID-19 has created the longest waiting list on record

Under the NHS constitution, patients are entitled to start non-urgent treatment within 18 weeks of referral into a consultant-led service. The waiting list is made up of patients who have been referred under this standard, including those waiting at every stage of the care pathway – from referral through diagnosis to treatment.

The waiting list was already growing prior to COVID-19. In the 5 years before the pandemic, the waiting list grew from 2.9 million pathways in January 2015 to 4.4 million by December 2019 – an average annual increase of almost 300,000 pathways.

The waiting list has grown by almost as much again during the pandemic, increasing by 1.2 million to 5.6 million in July 2021 – which means there are more patients on the waiting list than ever before (at least since the current records began in 2007). While the government has pledged an additional £9bn for tackling the elective care backlog, it also acknowledges the waiting list is expected to get considerably worse before it gets better.

1. 6 million fewer people than expected completed elective care pathways between January 2020 and July 2021

Patients come off the waiting list when they complete a care pathway – usually when definitive treatment starts, the patient declines treatment or there is a clinical decision that treatment is not needed.

The total number of completed pathways (admitted and non-admitted care) fell sharply in April and May 2020, as non-urgent elective care was postponed early in the pandemic. The NHS made considerable progress in restoring activity after the initial outbreak, but the second wave of the virus caused further disruption to routine care – albeit with completed pathways falling far less than might have been expected, despite extreme strains on the health service. The total number of completed pathways has steadily increased in recent months, but is yet to consistently reach – let alone exceed – pre-pandemic monthly totals.

Figure 1

Between January 2020 and July 2021, more than 6 million fewer pathways were completed than would have been expected based on 2019 numbers. This includes 4.6 million fewer pathways completed in 2020 and 1.6 million fewer so far in 2021 (January to July).

2. The backlog of elective care is not evenly distributed across England

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, there were consistent and growing inequalities in access to elective care in England. While the number of completed pathways fell everywhere during the pandemic, the scale of the backlog masks substantial variation between different parts of the country – and between and within regions.

Integrated care systems (ICSs) – area-based partnerships of health and care organisations – now cover the whole country. Each of England’s 42 ICSs looks after a local population of between 1 million and 3 million people. ICSs are expected to play a leading role in the recovery of elective care, with additional funding and support for innovation targeted at this level of the NHS. However, national data on elective care are not yet routinely published by ICS.

With the aim of analysing how elective care activity for each ICS has changed since 2019, we aggregated clinical commissioning group (CCG) data – which exclude the more specialised services that are commissioned regionally and nationally – to the latest ICS footprints. We took account of the considerable changes in the number and configuration of ICSs and CCGs since 2019 to look at activity over time on a consistent basis. Occasionally, hospitals do not submit data on elective care to NHS England. To ensure consistent comparisons over time, when a hospital did not submit elective care data to NHS England in a given month, we excluded the hospital from our analysis in that month across all years.

Our analysis suggests elective care activity fell in every ICS during the pandemic, but there were considerable differences between ICSs in terms of both the level of disruption and rate of recovery. The ICSs with the largest falls in completed pathways in 2020, compared to 2019, were in East London (37% fewer), Greater Manchester (34% fewer) and Suffolk and North East Essex (34% fewer). The smallest reductions were in Bath and North East Somerset, Swindon and Wiltshire (21% fewer), Mid and South Essex (18% fewer) and Nottingham and Nottinghamshire (13% fewer).

Figure 2

The numbers of completed pathways in some ICSs have now returned to (and in one ICS exceeded) 2019 levels. Between January and July 2021, the areas with the most completed pathways compared to the same months in 2019 were Nottingham and Nottinghamshire (4% more), Bath and North East Somerset, Swindon and Wiltshire (1% fewer) and Gloucestershire (4% fewer). The areas with the fewest pathways completed relative to the same months in 2019 were Herefordshire and Worcestershire (25% fewer), East London (28% fewer) and Birmingham and Solihull (33% fewer).

3. Patients living in socioeconomically deprived areas faced more disruption and delays than those in England’s least deprived areas

Elective care waiting lists grew more – and recovered more slowly – in certain areas of England. The purpose of calling attention to these differences is not to rank or assess ICS performance, but to highlight how different ICSs began the enormous task of addressing the elective care backlog from very different starting points. Every ICS works in a unique context, with different needs, challenges and resources.

Pre-existing inequalities shaped people’s experiences of the pandemic and elective care is no different. To analyse the varying impact, we grouped all ICSs into quintiles based on Index of Multiple Deprivation scores – which rank every part of England from most to least deprived.

We found that the pandemic disrupted routine hospital services throughout England, but patients living in the most socioeconomically deprived parts of the country experienced more disruption to their diagnosis and treatment. On average, numbers of completed pathways fell further – and has been slower to recover – in the ICSs that cover more socioeconomically deprived parts of the country than in the least deprived areas.

Figure 3

There is also considerable variation within and between the different regions of England. This echoes earlier analysis, which found a small but significant deprivation gradient for hip replacements, with people living in the most socioeconomically deprived areas more likely to be impacted by delayed or cancelled care.

Differences in local rates of COVID-19 are likely to have been another important factor – albeit one closely linked to and shaped by the inequalities that existed long before the pandemic.

4. The elective care backlog is likely to get worse before it gets better. But how bad might it get?

The government acknowledges the waiting list for elective care is likely to get considerably longer and Sajid Javid has even warned that the list ‘could go as high as 13 million’ – a prospect described by the Institute of Fiscal Studies as not ‘beyond the realms of possibility.’

Under the government’s ‘Building Back Better’ plan for health and social care, an additional £9bn has been committed to support the NHS to increase elective care activity to around 130% of pre-pandemic levels by 2024/25. While recovering the 18-week standard by 2024/25 is projected to require closer to £17bn over this parliament, this is still a huge sum.

Nevertheless, the government has repeatedly declined to commit to a timetable for clearing the backlog. The primary reason for this is likely to be the uncertainty over ‘missing patients’ – people who did not or could not seek care since the start of the pandemic and have therefore not yet been added to the waiting list.

Figure 4

In 2020, 5.9 million fewer people were added to the waiting list than in 2019. Between January and July 2021, 1.6 million fewer people started a new pathway compared to the same period in 2019. On this basis, there could now be a total 7.5 million ‘missing patients’ who have not started a pathway potentially leading to routine hospital treatment. And this may be an underestimate, as demand for elective care was projected to rise prior to the pandemic.

While the number of new pathways being started has been much closer to 2019 levels in recent months, there so far appear to be few clear signs of the missing patients presenting in large numbers.

5. Some parts of the country may have more missing patients than others

Starting a pathway does not always end in treatment, so not all of the missing patients will need care if their health concerns have already been resolved via another route. However, there are concerns that the health of those who do present may have seriously deteriorated in the interim – so could need more urgent, more intensive treatment.

How many of these missing patients will eventually present, and what treatment will be needed by those who do, is a big unknown. This uncertainty has major consequences for the time and funding needed to address the elective care backlog.

This uncertainty may pose additional challenges with scheduling treatment and getting the most from the available capacity – for instance, if patients needing urgent care have to take priority over patients whose needs are less urgent, but for whom a long-awaited procedure will be life-changing. Our analysis indicates significant variation between ICSs in terms of the numbers of missing patients and the speed with which the number of new pathways is being restored to pre-pandemic levels.

Figure 5

The ICSs with the largest falls in new pathways in 2020, compared to 2019, were Northamptonshire (39% fewer), North London (35% fewer) and East London (35% fewer). ICSs in Mid and South Essex, Nottingham and Nottinghamshire (both 17% fewer) and Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly (20% fewer) saw the smallest reductions in the same period.

There may also be some indications that missing patients are returning faster in some ICSs than others. Between January and July 2021, Mid and South Essex (8% more) exceeded the number of new pathways in the same months of 2019 and ICSs in Coventry and Warwickshire and Gloucestershire came very close (both 4% below). Relative to the same period in 2019, ICSs in North London (28% fewer), North West London (25% fewer) and Lincolnshire (23% fewer) had the fewest new pathways started in this period.

As above, ICSs all work in unique contexts and face different challenges. Most new pathways begin with a GP referral, and GPs working in more socioeconomically deprived areas tend to have more patients to look after. On average, the number of new pathways fell further – and has been slower to recover – in the ICSs that cover more socioeconomically deprived areas.

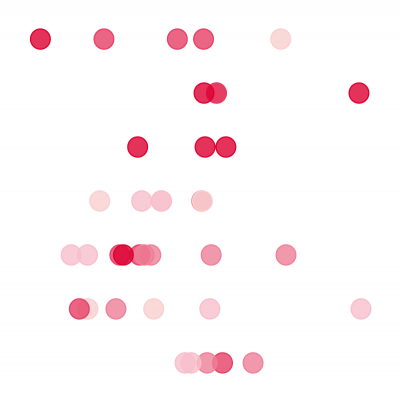

Figure 6

Conclusion

The NHS was already struggling to keep pace with the growing demand for elective care prior to the pandemic, largely due to staff shortages and limited hospital capacity. COVID-19 has made the situation considerably more difficult.

The pandemic has severely disrupted elective care. As well as the number of patients in hospital with COVID-19, the need to separate patients based on their COVID status and to implement social distancing measures has had important consequences for hospital capacity. Protecting patients and staff with extra infection prevention and control measures has increased the time needed to deliver key diagnostic and treatment procedures, reducing productivity. And NHS staff having to take time off work due to COVID-19, through sickness or self-isolation, has limited the workforce available to provide care.

While COVID-19 affected routine hospital services throughout England, patients living in the most socioeconomically deprived parts of the country experienced more disruption to their health care. Untangling the reasons for these disparities is complex, but the essential point is that they exist. Efforts to tackle the elective care backlog will need to target resources and support towards the patients, services and parts of the country that have been worst affected.

However, the pandemic has also impacted health and social care services more widely, with the broader picture one of major delay, disruption and increased demands on all services. This summer, GP practices and A&E departments have reported very high levels of demand for a wide range of urgent health problems. With winter looming, and concerns about a resurgence in seasonal flu alongside a possible increase in COVID-19 cases, ambitions for tackling the elective care backlog will need to be weighed against a range of other important priorities.

Tackling the backlog to get patients treated and restoring elective care to pre-pandemic levels is likely to take years. Doing so equitably – and without sacrificing the broader ambitions to modernise care in the NHS Long Term Plan – is likely to be one of the defining challenges between now and the next general election, and almost certainly beyond.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more