Why is the NHS really under 'record pressure'?

12 March 2022

With the emphasis now on living with COVID-19, the public might expect NHS performance in England to improve quickly. NHS performance statistics, however, continue to paint a bleak picture. The health service’s experience this winter, even before the Omicron wave, signals just how much of a challenge lies ahead in tackling the backlog of non-COVID care while still treating a substantial number of COVID-19 patients.

The reasons for these struggles may seem obvious, but a closer look reveals a more complex picture. A good understanding of these pressures is crucial to help managers and policymakers make informed decisions and manage public expectations.

In this analysis we compare data across a range of services in winter 2021/22 against winter 2019/20. We take winter as starting from November and running up to the latest available data. For some services that is February, for others it is January (in the case of IAPT it is December).

Record pressure on the NHS going into winter?

In November and December 2021, even before the Omicron variant peaked, the NHS in England was repeatedly described as under ‘record pressure’. Performance data tell a clear story of rising pressures, with longer waits and other red flags of declining performance. This was the case for services associated with hospital care, although primary care and IAPT services for mental health seemed to recover (possibly because these services can be delivered by phone or online).

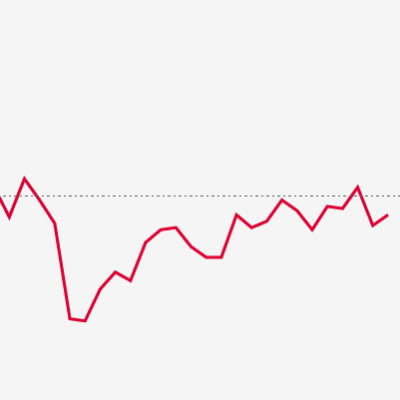

Performance for hospital services was not just poor but the worst in recent history. Only 73% of people attending A&E departments in December 2021 and February 2022 were seen within 4 hours, the joint lowest figure in 10 years of available data (see the chart below). This was not just the case for emergency care. Only 63% of patients waiting for an elective (planned) treatment in February were within 18 weeks of a referral compared to a target of 92% – performance during the pandemic has been the worst performance since the very first months of recording. These figures suggest winter 2021/22 was among the most challenging months the health service has seen in decades.

Why is the NHS under such pressure?

A mixed outlook on activity

The most obvious explanation for these pressures is higher demand for services. Although the NHS was described as ‘busier than ever’ going into winter, looking across different services it was not a straightforward picture of more patients than ever being seen or contacting the NHS. While the numbers of people contacting NHS 111 and phoning for an ambulance were above pre-pandemic levels – and at historic highs – other measures of activity, such as elective care and emergency admissions, remained at or below those seen in 2019.

Fewer beds, higher staff absences but a larger workforce

A second possible explanation is supply shortages. The UK entered the pandemic with lower health care spending per person and fewer staff and beds compared with other wealthy countries in the OECD. There were 100,000 vacancies in December 2019, rising to 110,000 in December 2021. During the pandemic the NHS has had to cope with both the direct impacts of treating COVID-19 patients and the indirect impacts, including reduced hospital bed capacity because of enhanced infection prevention control measures and increased staff absences. All were evident heading into winter 2021/22, with more COVID-19 patients compared with the preceding summer, as well as fewer beds and more staff absences than before the pandemic.

However, that does not tell the whole story. The NHS’s struggles this winter started before COVID-19 hospitalisations from Omicron peaked in late-December – indeed performance against the 4-hour waiting times target was already at a low in October. Moreover, the NHS workforce has increased significantly in part owing to funding committed alongside the NHS Long Term Plan. In October 2021 there were 1.2 million full-time equivalent staff (FTEs) working in hospital and community health settings, 8.1% more than in 2019. Even adjusting for the higher absence rate, staffing was 6.9% higher than October 2019 (indicative estimate only, see chart notes).

Disruptions to care

Neither demand nor supply factors alone explain the extent of the pressures facing the NHS. The explanation is more complicated and has to do with the flow of patients through the health care system, and the ability of the system to ensure supply meets demand when it is under pressure and care is disrupted.

Before the pandemic the NHS was considered a lean service, with a low length of stay in hospital and a high occupancy rate compared with other similar countries. This means it was using resources intensively but with little spare capacity. This works so long as patients move quickly through the system, like cars moving quickly on the motorway; but, to continue the traffic analogy, the NHS was like a busy road vulnerable to disruption.

The pandemic continues to impact the health and social care system, in terms of ongoing cases of COVID-19, increased complexity of patients and significant backlogs of care needs across services. This has disruptive knock-on effects that are cumulative and can lead to a downward performance spiral (see below). So, in one scenario:

- unexpected demand from COVID-19 emergency admissions puts pressures on beds

- in turn this leads to cancelled planned treatments

- with long waiting lists for treatment, patients’ conditions deteriorate and severity increases

- leading to pressure on primary care, NHS 111 and ambulance services

- patients who would have received planned care end up being seen in emergency settings instead, where it takes longer for their care needs to be met.

Importantly, these disruptions need not be limited to COVID-19 or even health care. Adult social care is also under pressure, but, unlike health care, has seen staffing numbers fall this year (estimated to be more than 4% down in January 2022 compared with March 2021) and reductions in care home beds. Other pressure points include:

- a backlog in primary care that means staff have less time to proactively manage long-term conditions

- hospitals finding it difficult to discharge patients owing to pressures on adult social care and backlogs in community care

- a lack of free beds meaning ambulance crews find it more difficult to handover patients, which results in longer response times and increased calls from patients waiting for care

- staffing pressures, including higher absence and vacancy rates, that mean there is more of a reliance on trainees, agency staff and locums operating in unfamiliar settings or roles.

All these pressure points contribute to mismatches in supply and demand, longer stays in hospital, pressure on beds, sub-optimal care, and general disruption across the system. Action will be needed across the health and social care system to get back to meeting performance standards.

The long road to recovery: what next?

As the NHS moves out of the Omicron wave, attention will turn to recovering services. The public may anticipate that as the burden of COVID-19 lessens, things should immediately get easier and the NHS will start to make inroads on the waiting list – as envisaged by the elective recovery plan. But our analysis of data from this winter suggests the NHS will remain fragile for longer, amid ongoing COVID-19 admissions, and as disruptions to care and backlogs of care needs from the pandemic play out.

Looking further ahead, demand for care is only anticipated to grow over the next decade. To lessen the impact of future shocks to the NHS, policymakers should plan a more resilient service. As a starting point that may mean, after decades of decline, an increase in the bed base – as recognised by the former Chief Executive of the NHS, Simon Stevens – and a proper workforce plan to deliver the staff the NHS needs. In the meantime, the government needs to be realistic about the time and resources required to recover services.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more