The nation's health

Priorities for the new government

The nation's health

19 November 2019

About 11 mins to read

Key points

This long read was produced during the 2019 General Election.

- A healthy population is one of the nation’s most important assets. It is valuable in its own right and also creates value for society. It allows people to participate in family life, the community and the workplace.

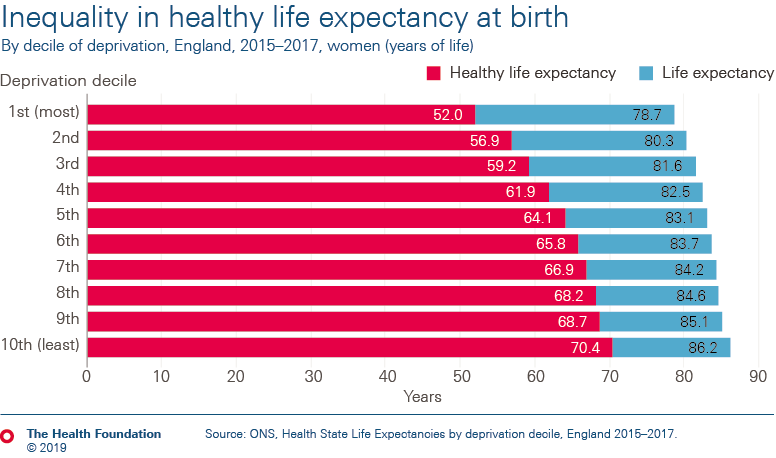

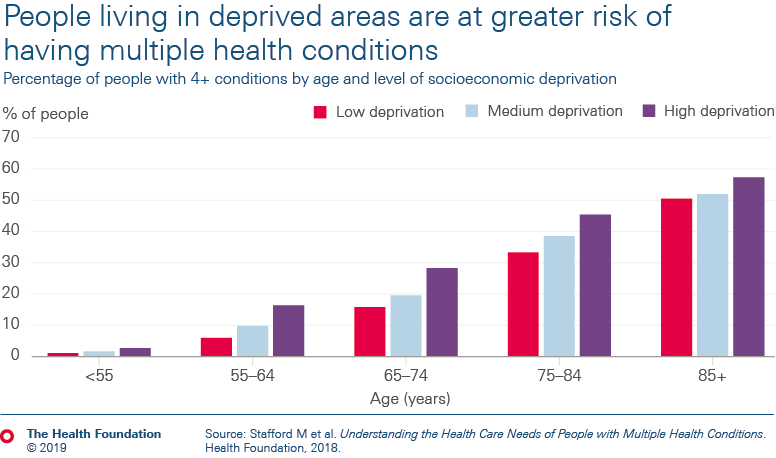

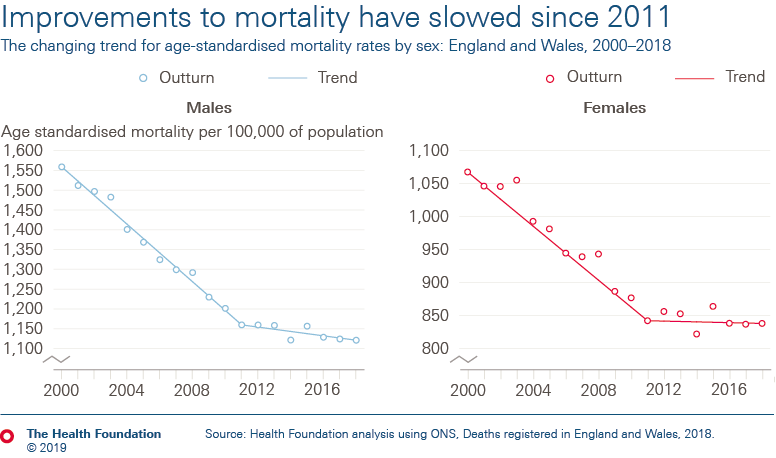

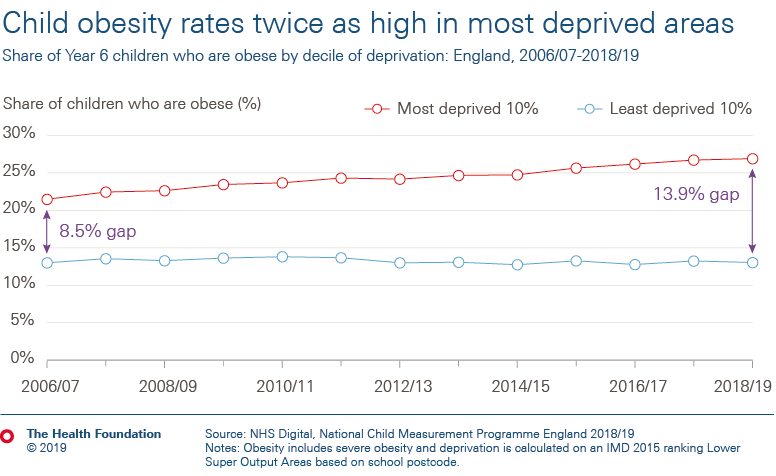

- Long-term improvements in life expectancy and mortality in the UK have stalled and are falling behind other high-income countries. At the same time the difference between the health of people living in the best- and worst-off communities is widening.

- Action is needed across the whole of government to address these trends. Investment needs to be directed towards areas of public spending that create the right conditions for people to lead healthy lives.

- Stronger measures are needed to ensure that government is held to account for the health of the population. This should include adopting a legislative framework, along the lines of the Welsh Wellbeing of Future Generations Act to encourage long-term action across government to promote good health. It should also include establishing an independent body to track and analyse trends in mortality and morbidity.

- Similarly, the way success is measured nationally needs to change, moving beyond GDP to evaluating policy on the basis of health and wellbeing as a primary measure of successful government.

The nation's health

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more