The healthy life expectancy gap Unpicking the latest ONS data on healthy life expectancy

14 December 2018

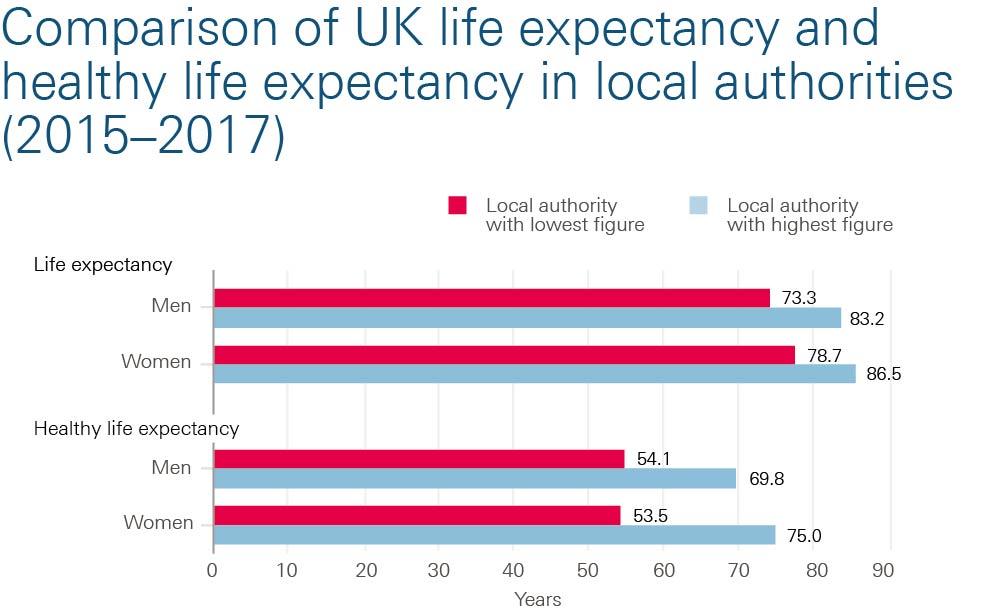

It’s well known that people living in different areas of the UK have different life expectancies. A boy born this year in the Hampshire district of Hart can expect to live for 10 years longer than a boy born in Glasgow City. This week’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) release sheds light on an even greater, but less discussed, inequality: the variation in healthy life expectancy (the years people can expect to live in good health).

Unpicking the data

The latest ONS data looks at the 2015–2017 period. A girl born in the Orkney Islands can expect to live 75 years in good health, but she would live only 53.5 years in good health if she was born in Nottingham – a 21.5-year gap. That’s a staggering, more than two-decade difference in the years of life spent in good health for women. A similar difference is also seen for men (a gap between local areas of 15.8 years), as the figure below shows.

The inequality in expected years of good health is starker still if we consider that those with a shorter life are also more likely to spend a greater period of that life in poor health. A girl born in Nottingham is expected to spend 34% of her life (27.6 years) in poor health, whereas a girl born in the Orkney Islands is expected to spend 8% of her life (6.7 years) in poor health.

These inequalities are nothing new. Differences in health outcomes across geographic areas have long existed. Worrying new trends, however, are emerging. The most discussed has been the slowdown in improvements in life expectancy since around the turn of the decade. Healthy life expectancy isn’t even keeping pace – it has actually fallen for women in the UK by 0.2 years since 2009–2011. That’s had the knock-on consequence of closing the gender gap. Men are starting to catch up, but for the wrong reasons.

It's worth noting that the ONS data allows us to compare the changes in healthy life expectancy across local areas in England between 2009–2011 and 2015–2017. Of the 150 local areas for which there are estimates, 37 have recorded a statistically significant reduction in healthy life expectancy (and 77 have recorded reductions overall). Women in Nottingham experienced the greatest fall in healthy life expectancy at birth: a reduction of 6.1 years.

The healthy life expectancy measure captures people experiencing poor health at any point in their lives and for any length of time – it doesn’t necessarily all come at the end. It is also calculated on a ‘period’ basis. That is, they assume that a child today will have the same risk of death, or period of ill health, at 80 years of age as an 80-year-old does today (in a given area). While we might expect improvement by the time that child reaches 80 years, it is the extent of the variation in years of life and those spent in good health that matter here.

How can we achieve change?

While the trends mentioned here make for grim reading, the future need not be so bleak. For one thing, the levers of change are relatively well known and are already within domestic control. Neither are these trends entirely off the government’s radar. With the UK’s population ageing, the government’s Industrial Strategy has a mission to achieve a 5-year increase in healthy life expectancy by 2035 and narrow the gap between the richest and poorest areas. This theme is also picked up in the Department of Health and Social Care’s vision for prevention, which sets out areas for action to try and meet this challenge.

Addressing the social determinants of our health – including the quality of the work we do, the housing we live in, our access to affordable, healthy food, and public transport links – will be key. Regulation can play an important role in these areas, but reductions in local-authority funding and ongoing cuts to working-age welfare risk undermining even the maintenance of people’s health.

There is much to do if people’s health is to be improved and the huge inequalities in health outcomes closed. Addressing areas that require investment will need to be a key theme of the 2019 spending review, alongside a wider cross-government commitment to the maintenance and improvement of the UK’s health.

David Finch is a Senior Fellow at the Health Foundation.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more