Prioritising the nation’s health as an asset

26 November 2018

Good health has a significant influence on people’s social and economic outcomes. It affects people’s wellbeing and productivity, as well as a country’s output potential and social cohesion.

Despite this, the recent deterioration in key indicators of our health – stalling life expectancy improvements and widening health inequalities – has received far less scrutiny than the poor performance of indicators of prosperity, like household income or productivity.

This year’s Autumn Budget provided a boost to incomes through tax and benefit changes and found additional funding for the NHS, an institution focused on reacting to health problems. However, funding for the parts of government that support the maintenance and improvement of health – including education, local government and transport – are set for further real-terms cuts.

Investment in maintaining good health throughout our lives continues to be under-prioritised. So why are we failing to treat our health as a national asset that requires investment, and what are the consequences of this approach?

Measuring success

It doesn’t help that many of our society’s metrics for success are framed around the economy – be it GDP, employment or pay. Clearly, incomes are an important determinant and proxy of prosperity, but a strong focus on such targets can distort the original intent of policy too.

It’s encouraging to see increasing awareness and development of wider measures. For example, the Office for National Statistics now provides an annual measure of wellbeing in the UK, and human capital measures are being developed. The World Bank recently published the Human Capital Index, which is designed to encourage developing countries to invest in the health and skills of their population.

The index also allows us to consider the gap in productive potential between and within nations. For example, viewed through this framework the 15% survival gap from age 15 to 60 between men in the most- and least-deprived fifth of England and Wales translates to a 29% loss of productive potential. The shorter lives of men from the most-deprived backgrounds have serious economic, as well as individual and societal, consequences.

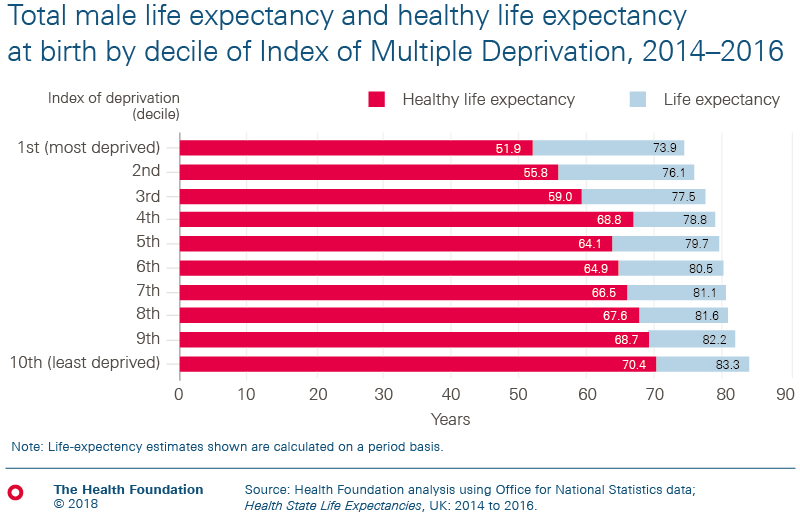

Ensuring people live long lives in good health is becoming increasingly important to the UK government as our population ages. Reflecting this, the Industrial Strategy sets out a mission to achieve a 5-year increase in healthy life expectancy by 2035, boosting the available workforce. Tackling the wide inequalities in health outcomes that exist in this country – an almost 19-year gap in years lived in good health (see chart below) – will be crucial to achieving this aim.

Future focus

So far, the policy response appears focused on supporting older age groups. However, maintaining health across the life course starts from the youngest ages, beginning with the first 1,000 days of life. Our long-term health is determined by the conditions in which we are raised and live – the quality of our housing and work, our education, local surroundings, and the food environment. These are the social determinants of health.

Political decision-making, though, tends to prioritise near-term reward. Making commitments to long-term investment in any area of public policy can be difficult. Maintaining and improving health can be particularly problematic, because doing so requires action across a range of areas. The policy levers for change are often held in the hands of people with aims other than improving health. Concerted cross-government action, at the national as well as local level are key. Decision-makers should be encouraged to look beyond their narrow responsibilities and act holistically.

The Social and Economic Value of Health

The Health Foundation is funding a £2 million programme of research in six UK universities that will run over the next 3 years. The programme will assess the social and economic value of health for individuals, using innovative methods to isolate the causal impact of health on wider outcomes. Initial findings are anticipated in 2019.When assessing our society’s prosperity, government decision-makers need to look beyond purely financial measurements of success and begin to view health as an asset. It is a stock worth investing in and can be improved at any age by a healthy environment.

We at the Health Foundation want to see more action on the strategies that help people stay healthy. Crucial to making progress on this will be developing a better understanding of the value of people’s health to wider social and economic outcomes.

David Finch is a Senior Fellow at the Health Foundation.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more