NHS winter pressures: Going into hospital

15 December 2017

This is the second blog in a Health Foundation series looking at winter pressures on the health and social care system in 2017/18. In the first blog, Dr Becks Fisher looked at how the NHS is aiming to help us stay well in winter and thereby reduce pressure on hospitals. In this second blog, Tim Gardner looks at what is happening at the front door of hospitals this December.

When you hear the words ‘winter pressures’, what comes to mind? An internet search reveals images of ambulances queuing outside hospitals, long waits in packed emergency departments, and patients on trolleys waiting for beds. So how will the NHS cope with what this winter might bring to the front doors of hospitals in England?

Ambulance response targets

Targets for ambulance response times have been overhauled in the last year, aiming to make sure patients receive the most appropriate form of emergency response. Unfortunately, the phased roll out of these changes across England’s 11 ambulance trusts means there is no comparable national data on response times. The six trusts still reporting against the old targets generally performed worse in October 2017 than in October 2016. This should, however, be seen in the context of rising demands on the ambulance service, which has had to cope with substantial increases in calls in the past 12 months.

The 4-hour A&E target

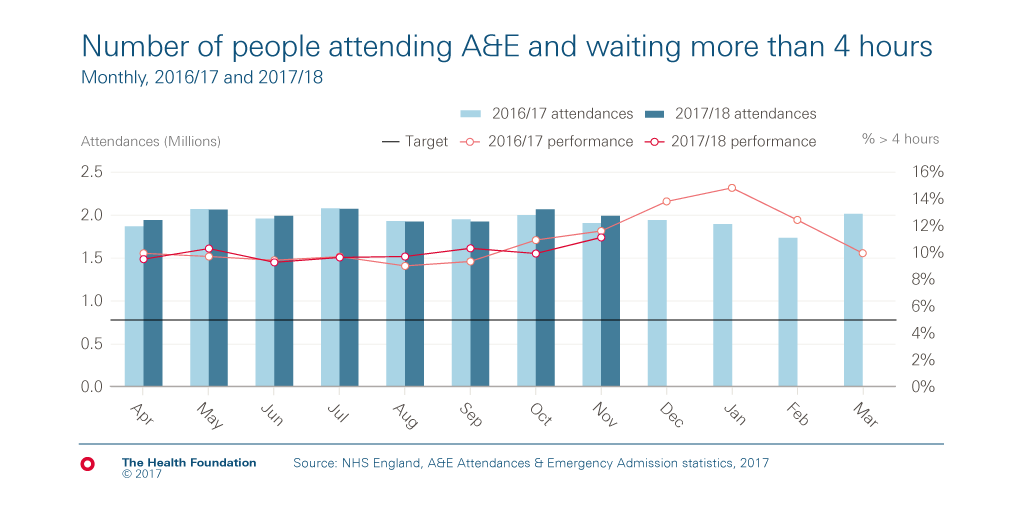

Hospitals are expected to admit, discharge or transfer at least 95% of patients within 4 hours of arriving in A&E, but this hasn’t been achieved nationally since 2013/14. Last year saw a big drop in performance on this 4-hour target: 89.1%, down from 91.9% in 2015/16. It was the worst year since records began (in 2003/04).

So far in 2017/18, the percentage of people waiting longer than 4 hours has followed a similar path as last year, though recent projections suggest it could get slightly worse.

Growing demand is part of the cause of rising A&E waiting times, with the number of people who attend A&E having increased at a faster rate than the population has grown. By the end of November 2017, 16 million people had visited an emergency department in England: more than the same period in 2016/17, but only by 211,774 or an increase of just 1.3%.

Primary care streaming

This year’s national winter plans aim to divert people with urgent but more minor conditions away from A&E, as discussed in the first of our winter blogs. ‘Primary care streaming’ means that those who go to A&E may find themselves being treated by primary care clinicians, who have been brought in to allow emergency care specialists to focus on more critically ill patients.

An injection of £100m capital funding was made to support the implementation of primary care streaming in every major A&E ahead of this winter. NHS England believes this is a safe and effective way of managing demand within A&E. However, the evidence base seems weak and finding enough clinical staff will be difficult given the shortage of GPs. Primary care streaming could also have unintended consequences if people begin to perceive going to A&E as more convenient than seeing their local GP.

The relatively small increase in A&E attendances so far this year could be linked to efforts to offer care elsewhere, but it’s still early days. Our report, A clear road ahead, finds that previous interventions to divert demand away from hospitals haven’t had much of an impact. It’s also possible that longer waits have discouraged people with less urgent problems.

Seasonal pressures on A&E

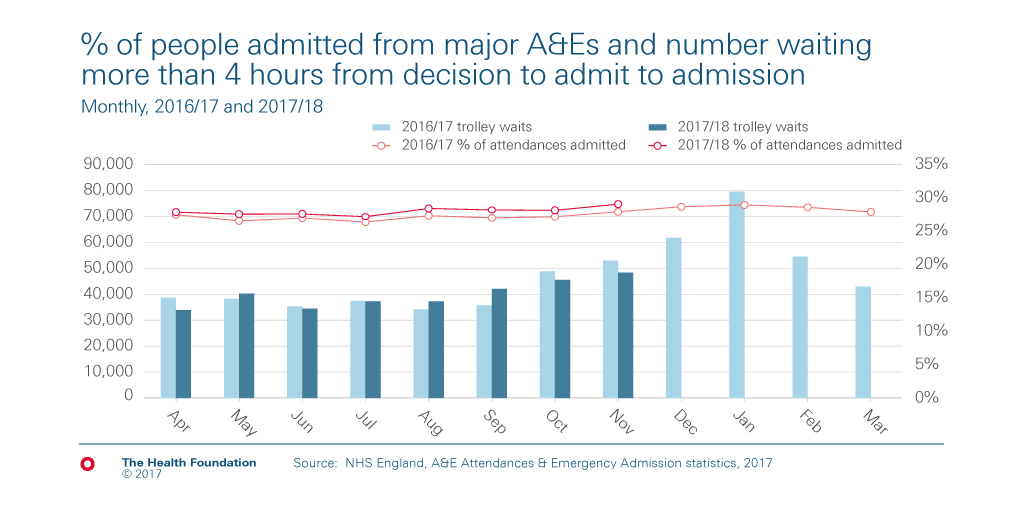

Fewer people attend A&E in winter than at other times of the year, so seasonal pressures are about more than numbers. More people who do attend A&E need to be admitted to hospital as an emergency, which adds to the pressure on front-line staff and hospital capacity.

This is reflected in the percentage of attendances at major A&E departments that result in an emergency admission. This increased from 19.1% in 2002/03 to 27.5% in 2016/17 and, based on the first 8 months of 2017/18, is on course to be about a percentage point higher this year. This is despite recent research that suggests patients who are now being discharged from A&E would probably have been admitted a few years ago.

The wait for a bed

More emergency admissions mean more pressure on inpatient beds. Delays in admitting people from A&E to a bed have grown considerably in recent years. However, the number of people waiting more than 4 hours from a decision to admit to being admitted to a bed is currently similar to the same point last year.

Increased demand for emergency care and the growth in emergency admissions have consequences beyond A&E. Hospitals open extra beds to cope with high demand, but the lack of space and staff shortages mean emergency patients are sometimes admitted to beds normally used for non-urgent treatment. Some beds are ringfenced for planned treatment (including elective surgeries such as hip replacements), but emergencies understandably take priority.

The wait for consultant-led treatment

Unfortunately the demand for beds means longer waits for people needing planned treatment. These cases may be less urgent, but patients are waiting longer, potentially in pain and discomfort. NHS targets require that at least 92% of people waiting for consultant-led treatment should wait less than 18 weeks from GP referral to starting treatment. This target hasn’t been met since February 2016. In October 2016, 90.4% of people had waited less than 18 weeks, which fell further to 89.3% in October 2017.

As more people are being referred for treatment than are being treated, the total number waiting is also getting bigger. The total number of people waiting hit 3.9 million in November 2016, which grew to 4.1 million in November 2017.

Winter pressures mean cancelled operations

More emergency admissions can result in planned operations being cancelled at the last minute for non-clinical reasons – anything from administrative error to operating theatres being used for emergency patients. So far this year, 37,340 elective operations have been cancelled – slightly fewer than the 38,176 cancelled in the same period last year, but similar as a percentage of all elective admissions.

Pressures take their toll

Overall, it’s hard to conclude that the NHS is in a fundamentally better place compared to this time last year. More people are going to A&E, more people wait longer and more are admitted – not drastically more, but enough to ratchet up the pressure on already overstretched services.

How does more pressure at the front door affect what happens inside hospitals? This is the subject of our third blog of this winter series.

Tim Gardner (@TimGardnerTHF) is a Senior Policy Fellow at the Health Foundation

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more