Health investment needs long-term thinking

10 July 2018

Investing in public health pays off down the line. As the government seeks to restore NHS funding it cannot also ignore this vital policy area.

In the year of its 70th birthday the NHS has quite rightly been made the centre of attention. A government commitment to boost NHS funding is a welcome early present, even if, as Health Foundation analysis has shown, the 3.4% increase promised will at best stem the decline in services.

But before the celebrations get fully underway, the latest release of local authority revenue expenditure data by MHCLG provides a reminder that when we talk about health we shouldn’t just think about health care. On a like-for-like basis the public health grant – for local authorities to provide prevention and health services – has fallen by £0.4bn in real terms, to £2.4bn, in the last four years. That translates to a 17% fall in spend per head between 2014/15 and 2018/19.

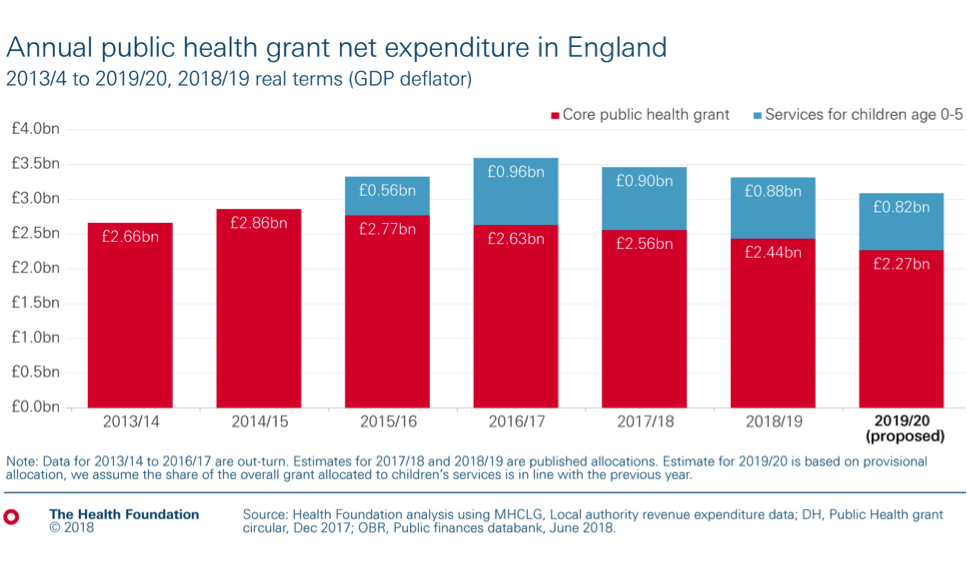

On the face of it the overall allocation in 2018/19 of £3.3bn is higher than four years ago, but as the chart below shows, that total includes £0.9bn for services for children aged up to five, an area of spend transferred from the NHS part-way through 2015/16. Looking forwards, if provisional allocations for 2019/20 go ahead, funding per head would have fallen by almost a quarter (23.5%) by 2019/20.

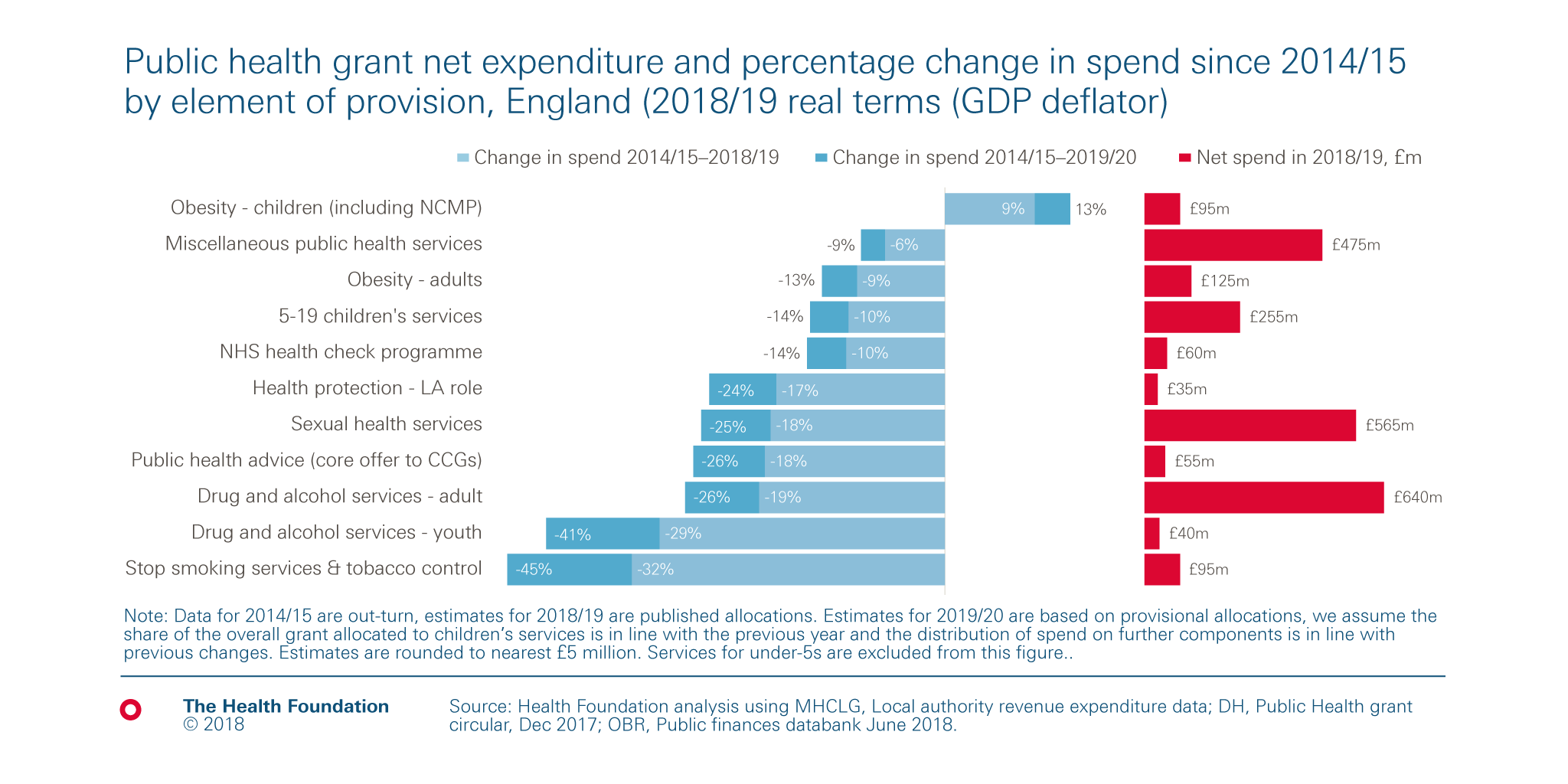

Where those cuts fall will have important implications for our nation’s health, and potentially demand for health care further down the road. As the next chart below shows, in almost every area of provision spending has fallen since 2014/15. The two largest areas of spend, drug and alcohol services for adults (£640m) and sexual health services (£565m) have seen real terms reductions of a fifth (19% and 18% respectively) between 2014-15 and 2018-19. That could become 26% and 25% next year if further cuts are allocated across services in the same pattern.

To some extent re-allocation of spend could reflect falling need or changes in methods of treatment and prevention. However the scale and pace of cuts to stop smoking and sexual health services are greater than reductions in the prevalence of smokers and STI diagnoses rates which may indicate this is not related to falling need. Indeed, the reduction in STI diagnosis may be a result of lower funding. Problems related to drug and alcohol use are likely to be deeply entrenched. Meanwhile funding for children’s services has fallen by 10% over a period where the population has grown by almost 4%.

There is one potential route to boost public health funding; the government still intends to allow local areas to retain a greater share of revenues raised through business rates. But too great a reliance on such powers will ultimately be counterproductive. The areas with the worst health outcomes are likely to be the most deprived with less ability to raise funds locally. Central government will still need to distribute the right level of public health grant in the right way to reduce health inequalities.

When setting out details of the NHS funding boost, the prime minister promised that the detail on public health would come at the 2019 spending review, although the autumn Budget is likely to set the envelope. She also highlighted a need to focus on prevention, which at a very minimum means investing in public health. The Health Foundation has estimated that simply maintaining current provision of public health (including the public health grant and Public Health England’s budget) in line with the wider NHS budget will require a real-term spending increase of £2.6bn a year by 2033/34.

We know the right public health interventions can provide benefits at least equal to health care, implying a strong case for additional investment. However, there is a need to go further, look beyond prevention and tackle the causes of the causes of poor health.

A long-term plan that truly invests in the health of the population means recognising that good health supports positive social and economic outcomes for both people and places while reducing inequalities in the social determinants of health. These are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age such as, our housing, education and training, transport networks, and the work we do.

Many of these factors have come under pressure as spending on public services and working-age benefits have been dramatically reduced over the last eight years of austerity.

The autumn Budget and following spending review will provide an opportunity to redress this balance, provide additional funding for public health, and more widely, the social determinants. There is a clear fiscal case for taking upstream action to improve health, rather than reacting to ill-health through healthcare provision, especially with health-related pressures set to bear on the longer term public finances. But more importantly it would send out a clear signal that the government values our good health and the economic and societal benefits it brings.

David Finch is a Senior Fellow in the Healthy Lives team at the Health Foundation

This blog first appeared in Public Finance

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more