Health is wealth? REAL Challenge annual lecture

Wednesday 9 November 2022, 11.00–12.30

Andy Haldane

The last time I was on a podium like this, actually a few weeks ago at the University of Glasgow, halfway through the Prime Minister resigned. That's not the plan today as I understand it, but you never know, depends what I say.

Jennifer, thank you for your kind intro and also for your bravery in asking me, someone who knows very little about health to give a Health Foundation lecture about health and the economy. And that is the link today. I'm meant to know something about the economy, and today, building on the great work the Foundation does, that the REAL Centre does, I want to argue not only that those links between health and the economy are deep-seated, but even more importantly that they've never been more important than deep-seated than just at present. And then suggest perhaps tentatively a few ways in which both health and the economy might be improved. That's roughly the order of play.

So for those who've had the misfortune of reading my previous speeches, you'll probably know that I like nothing more than to torture a metaphor. And today will be no exception to that rule. And the tortured metaphor today will be about society's immune system, its weakness. I'll get there via a Netflix documentary. How many of you saw the Netflix documentary on Sunderland football club? Anyone else see that? Just me as it turns out. and Anita, two people. I was actually born in Sunderland, I am a Sunderland football club supporter, you should all go out and watch some more telly. So towards the end of that documentary, this is some weeping Sunderland supporters as their team, my team, suffer their second relegation in two seasons. And the question they ask themselves, why is it always us? Why is it always us that suffers these indignities? And I thought that was a great jumping off point actually when moving from Sunderland football club to UK society. So we've been asking ourselves the same question now for at least a couple of decades, when these global shocks have come thick and fast, global financial crisis, COVID crisis, energy crisis right now, how is it that we in the UK always seem to cop disproportionately for those global shocks in terms of lost incomes, lost jobs and indeed lost lives?

Now having posed that question, there are at least two alternative hypotheses. The first of which is you've just been extraordinarily unlucky, right? A bit like Sunderland football club. We have been serial losers in life's lottery. That's one possible interpretation of the data. But there's a second, which I argue is much more congruent with the data, which is that this doesn't reflect bad luck but rather bad management at the policy level across a whole range of systems: economic, financial, social and indeed health. And that's the essence of what I mean by a weakened societal immune system; a failure to invest across those systems has resulted, as it would with a biological immune system, in what? A failure to grow at spritely rates, an increased susceptibility to shocks when they come along and an elongated period of convalescence in the event that those shocks come along. I think that's not the worst characterisation of UK PLC economically, socially and in health terms over the past decade. And sitting beneath it is a weak and weakening societal immune system.

So leaning into this a bit more, I'm going to think about health and other systems through a systems lens using the analytical apparatus of complex systems thinking. Because one conception of wider society is as a nested set of very tightly coupled, closely interlinked subsystems, I mentioned a few earlier on, economic, financial, social, community, health and others besides. And it's in the nature of complex, tightly coupled systems that they are only as strong as the weakest subsystem, just as a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. And that's meant as we've seen a progressive and continuing and perhaps even accelerating denuding of the resilience of the capitals that underpin our economic, financial, energy and health systems, what we've seen is structural subsidence in the strength of society’s broadly speaking immune system. Or put differently the way to conceive of health, as we do of other capitals in our economy and society, is as an endowment, as an asset, as a source of capital that needs continuous investment and replenishment if we are to grow, if we are to be resistant to future shocks and if our period of convalescence is not to be too lengthy. There's the punchline if you all fall asleep from here, that's the essence of it.

Here's the rough plan to give the illusion of structure to this lecture. I’ll talk a bit about the links between health and the economy, a bit about its resilience from a health care perspective. Then a bit about what we might do to strengthen that resilience both in health and beyond health as a set of nested subsystems.

Kicking off then with links between health and the economy. If you ever delve into a textbook in macroeconomics, which I would not recommend to any of you in this audience, you'll find that health at best plays only a bit part in the standard models and textbook treatments of what it is that drives the economy. And that's bizarre in a way. Because if you turned instead to economic history books, it's absolutely clear that health considerations are front and centre, have been front and centre in driving the inflection point in living standards and other things that we've seen over the last 250 years or so.

So economists like me, often for simplicity's sake, decompose the growth in economy's potential into two components. When driving forward how much we produce as an economy or society, that can be broken down into either increases in the number of people producing stuff – that is to say, growth in the labour supply – or growth in the efficiency or productivity with which those people produce. So economics, dead easy, sources of growth, two cylinder engines, either rises in labour market activity or rises in labour market productivity. Two cylinders of growth and viewed as such. It's absolutely clear that the inflection point in living standards after the industrial revolution had a very substantial health related dimension to it. The most obvious and direct has of course been that the workforce has expanded massively over that period contributing directly to growth in the economy's potential. And accompanying and indeed driving much of that has of course this been this very familiar improvement in health or the flip of that, rise in healthy life expectancy. It's been a global phenomenon, it's been remarkable, right, after literally millennia where life expectancy flatlined at about 40 years, that Hobbesian life, short and brutish, during the course of the 20th century we saw life expectancies more than double over that period. With that came increased labour supply and with that came increased economic growth. That's the first cylinder. And just as importantly, those improvements in health, those health advances were a significant, if not the most important, driver of the second cylinder of growth. That is to say productivity. We know from lots of evidence now that ill health, physical and especially mental, is a huge drag on workers' productive potential and therefore the improvements in health would've been a significant tailwind to productivity and growth over much of the period since the industrial revolution.

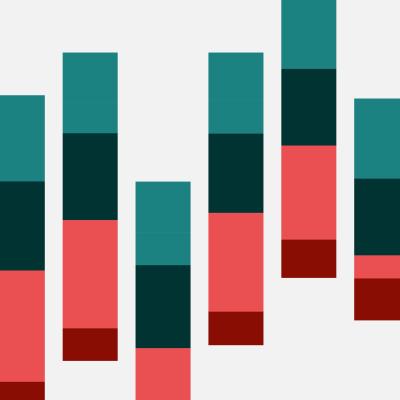

And the reason I’m mentioning those parts of deep history is because they're put in sharp relief by what we have seen during the course of the 21st century. After those three centuries, 18th, 19th, 20th of economics and health rising in lockstep, we've seen during the 21st century, a flattening and in some cases a reversal of those self-same trends. Everyone in this audience, we all know about Michael Marmot’s evidence on the slowing in increases of healthy life expectancy across the UK. We know that in some parts and for some cohorts across the UK, those HLEs are now falling in absolute terms for the first time in at least 200 years. This picture speaks a bit to that evidence and in lockstep with that, we've seen this – which is a rise in both number and proportion of the working age population that are reporting as long-term sick. Those lines are pretty flat but actual fact, it's pretty stark what we have seen over the past couple of decades since 2010, not so long ago those reported instances of long term sickness have risen a third from just over five million to around seven million. That is an absolutely staggering 17%, or one in six of the working age population, now reporting themselves to be long-term sick.

And when it comes to digging a bit beneath what's going on there, one of the most striking patterns looks at the distribution of this by age and in particular, the contribution made to this rise in long-term sickness by younger people, those in the 16 to 24 cohort, there the rise has been 50% rather than a third among that healthiest cohort. Now fully one in eight are claiming long term sickness. It's the orange line in this chart. We now see as much long-term sickness among those 16 to 24 as we have among those 25 to 49. And when it comes to understanding what's driven those trends, most of the survey evidence points fairly and squarely to the rising incidence of mental as well as some physical health problems among that younger cohort, both among women but more particularly among men. This chart just looks at some of those trends that will have translated not quite one for one, but nonetheless concretely into rising levels of inactivity among those youngest cohorts of the working age population. Now, and that in term will have served as something of a drag on the economy's economic potential, operating through that first cylinder, the first cylinder being labour supply.

Now the good news, the good news is in the period up to COVID, that dragging anchor from rising sickness and inactivity among young people was more than counterbalanced by rising participation in the workforce by those aged 50 to 64, the result of flexible working, elongating retirement ages and the like. In fact all in, the overall workforce rose by around three million people between 2006 and 2019. And just as well it did. Because if you decompose UK growth since the dawn of the global financial crisis into those two bits, rises in the workforce, rises in the productivity of the workforce, you find that pretty much all of the growth in the UK's economic potential has come from the first source rather than the second source. Productivity has flatlined over that period for the first time for at least 150 years. And therefore all the heavy lifting in driving growth in our economy has come from increased labour supply. And within that, the lion's share has come from this increased participation among older cohorts, particularly those in the 50 to 64 category. That was the single cylinder of UK growth, has been for much of the last 15 years.

Until recently, of course, because over the last couple of years in the light of COVID, we've seen even that prior trend go into reverse. Over the last couple of years we've seen participation trends among that older cohort, 50 to 64, go into reverse the all in decline in the UK labour force something like between half a million and a million people. I've put 650,000 here, roughly about right, of which the lion’s share has been in that 50 to 64 category. That's the blue bars in the bar chart here. And the significance of that of course is that the economic engine, having flown on one cylinder for most of the last 15 years, that single cylinder has now gone into reverse. We have seen a contracting workforce, when that expanding workforce had been the only factor driving growth in UK potential in much of the prior period.

There’s been an active debate, ongoing debate, about just what the root causes have been of that increased inactivity among the 50 to 64 year olds. You'll all be familiar with some of the studies that have come out over the past few weeks and months on that. For what it's worth, my reading of that evidence points I think pretty clearly towards the single most important factor being health. Here's a bit of survey evidence that speaks in that direction, asking for those inactive over this most recent period, the causes of that. And the red here is ill health, actually even that I think might understate the importance of ill health to this rise in activity. So the blue and the purple blocks here are retirement and caring for family in the home, for many of those people, their second cited reason for inactivity is also health related. So for me the evidence points pretty squarely to health having been the prime mover behind these trends. Indeed the story here is not so much as a pure COVID effect, this isn't a pure long COVID effect, this isn't the accumulated backlog of non COVID illness.

For me, the way to interpret this is to take us back to that complex system's lens on the problem. What we have had is a long standard, deep-seated secular trend towards ill health that I just mentioned, that's then been taken to its tipping point by the effects of COVID. Those tipping point properties are characteristic of complex adaptive social systems such as health. And I will argue that COVID was essentially the tipping point for that system.

In terms of what this means for the economy, well it makes a difficult situation even more difficult. What had been a headwind from young people, has now become a headwind from older people. What had been the single cylinder of growth in the economic engine has now gone into reverse gear. It should come as no surprise to anyone in this room that we therefore see macroeconomic headwinds such as a record number of unfilled vacancies. We haven't got enough people. That we should see staff shortages the length and breadth of the country in each and every sector of the economy. And of course, what those staff shortages will do is to accentuate and to elongate the cost of living crisis we are all living through. And even that, as if that were not bleak enough, probably almost certainly in fact understates the damage done by these secular trends in health. Certainly for people's wellbeing we know that ill health is a single biggest detriment to wellbeing. All the evidence suggests that COVID has caused a further down lurch in those wellbeing metrics. And all in, where this leaves us, is a situation where for the first time, probably since the industrial revolution, where health and wellbeing are in retreat, that having been an accelerator of growth and wellbeing for much the last 200 years, health is now serving as a break in rises in growth and in wellbeing of our citizens. That is the significance of this moment. That is why health matters, not just in some obstruse sense but particularly so given the confluence of trends and shocks we have faced over the recent period, which begs the obvious question, can we cope? In other words, is our health and health care systems sufficiently resilient to bear up to these trends? Some longstanding, some recent. You'll guess by the way I've toned that question, the answer's going to be no, isn't it?

Here's some diagnostics on that. I could picked loads. Many of these be familiar to many of you. You could look at those rising disparities in healthy life expectancy between different cohorts. This picture looks at that, we know there are profound differences in levels of HLE between different areas of deprivation of the country, that amounts now to around 15 years, to such an extent that you know in the most deprived parts of the UK, both men and women are living as much of a third of their lives in ill health. Absolutely remarkable. We know when it comes to spending on health care systems, at least by G7 comparisons, the UK sits towards the bottom of the pack, a bit like Sunderland football club, threatened by relegation from the G7. We know that when it comes to numbers of doctors or numbers of beds, the head of population, the UK, the red dot here occupies a relatively unenviable position after a number of years of relative under investment in both of those things. I think the King’s Fund estimated roughly a 50% fall in NHS beds over the past 30 years. We hear almost daily about the rise in waiting lists and the rise in waiting times for various forms of clinical intervention. This picture may double count, may overstate the rise, but nonetheless, the rise is unmistakable. For those waiting more than a year for treatment, we've seen those numbers rise from little more than 1000 in 2019 to something like 400,000 today. The most vertiginous of ascents. I could depress you further with diagnostics on this and maybe I will in the Q&A, but for now that's probably enough to I think to make the case.

On current projections, those problems in occupancy, those problems in satisfaction are unlikely to solve themselves anytime quickly. Most projections point them worsening over time. And what at root this points towards of course is the degree of resilience, the degree of redundancy in health and health care systems is being reduced, has been reduced progressively over time. The fragility of that system has increased over time and not just health systems. We know that aiding and abetting those rising fragilities in health, have been rising fragilities economically and socially as well. I mentioned some of the aspects of that too. We know that many of these health problems are seeded early in life among people in their thirties or their forties. Indeed often during the childhood years, it's therefore sobering context that UK PLC has levels of childhood poverty that do not bear favourable international comparison. It's relevant that when it comes to spending on children's services, we've seen not just a real decrease in that spending across all cohorts, that's comparing the red and the green bars here. But those cuts in spending on children and young people's services has been largest in the most deprived parts of the UK, to the point today that we spend no more on those services in the most deprived parts than we do in the least deprived parts of the UK. And if you went from children to more broadly based economic and financial fragility, we know that they have been high and rising for the better part of 15 years. Made worse no doubt by the ongoing cost of living crisis. And we also know from evidence, including from the RSA before my time, that that rising tide of economic and financial fragilities has shown up directly in those mental health problems in particular among younger people.

Enough diagnostically. Let's go to some prescriptions, on this, I am necessarily going to be a bit more speculative but I hope at the same time, still challenging to some degree. There is no single measure or policy that will turn the tide, that will strengthen the resilience of UK health and other subsystems. But from a potentially long list, let me just mention one or two that for me directionally would push us closer towards a somewhat more resilient picture than the one I've just painted. And the first point to make is a rather arid one, but I think nonetheless important one around measurement, if nothing else, COVID demonstrated the importance of effective measurement. If we are to put in place effective and timely remedial policy measures to such the point, we actually probably overshot the point where COVID stats were the news. The key point is to not lose sight of some of that when we enter peace time as distinct from war time. Because right now when it comes to keeping score on societal success, we give loads of focus to wealth but far less to health and happiness than figuring out how we're doing. And that for me needs fundamentally to change, that looking forward, a new national accounts would measure clearly and accurately all the capitals, not just human capital (people's skills), not just physical capital (machines and technologies), not just social capital (trust and relationships), but health is an endowment in capital as well and view them as one, as distinct but interrelated subsystems in securing and strengthening society’s immune system.

Second, in my previous gig at the Bank of England, I spent a lot of time thinking about the fragility of finance. One of the key lessons of the global financial crisis is if we are to adequately risk manage the financial system, we need in advance to subject that system to stress tests of various types, to figure out just how much redundancy and resilience it has. What is true of health, of finance is no less true of health, that was done in the teeth of COVID. It now needs to be systematised and regularised when it comes to assessing the resilience of health and health care systems. This is a place, Anita, Jennifer, where I think the Health Foundation and REAL could play a significant role on the measurement and analysis side.

There's some great work recently to go to my third bullet point. How long have I got, by the way? Haven't seen a card yet, one minute. I didn't see the 10 minute card, there you go. I will speed up on how devolution of health in Greater Manchester made a difference to health performance. Not surprisingly local problems, health or otherwise typically necessitate local agency and local information. This speaks strongly to us giving the hurry up and the giddy up to the agenda. Not just for health but for other reasons as well. Let me jump ahead a bit, give my one minute. On food standards, we have fallen well short of the recommendations set out by Henry Dimbleby last year. That feels to me, given these trends, like a hugely missed opportunity, one we can ill afford to miss looking ahead.

Given those trends in young people, is it the time to rethink about what is done in each and every school across the country? Is there a case for having a nurse in every school, not just providing if you like, the health education but the broader community and pastoral care that's needed in schools? A mini campaign that Sam Everington, architect of social prescribing, has spoken to. When it comes to business, and Jordan I'm sure speaks some more about that, we've seen business sitting up and paying much more attention to these matters over the past two or three years for understandable reasons, that needs to continue. This thing ESG, the environmental or social and the governance perhaps needs a letter adding to it, which is the health dimension, the raw responsibilities of business in securing the health, not just of their staff but of their customers, clients and communities as well.

We have, as we all know, an autumn statement coming soon. Some tough choices to be made, no doubt. One dimension of those is how when we're doing the budgetry arithmetic, we think about divvying up the spending between the current and the capital expenditure. This is super relevant because much of health spending falls into the former bucket, current spending rather than capital spending. But if you buy my diagnosis of how we should think about health, which is as an endowment, as an asset, as capital to guard against future health care problems, that allocation of spending may make much less sense. The right prism for viewing spending choices right now are the implications they have for long term wealth, health and happiness. And current fiscal distinctions do not make that distinction sufficiently precise or clear. Given my minus one minute, I reckon, I'll not dwell on the last aspect, which is rethinking and refashioning the protection we provide to people young and old when it comes to guarding against those financial and economic insecurities, which loom ever larger as they have over the past 15 years.

Let me wrap up. Does it matter, health? Of course it does, and of course it always has. But my reading of the runes is it's never mattered more than just at present. Given the secular trends and the more recent shocks that both our economy and health systems have faced, there's no question right now those health care trends are serving as a significant headwind to growth in the economy. They are amplifying that cost of living crisis. They're making more precarious our fiscal finances both today but particularly in the future. And ultimately, they're also reducing our susceptibility to future shocks. The one thing we say with certainty is that the future global shocks will come along perhaps even as thick and as fast as they have over the past couple of decades. We cannot afford to find ourselves in a similar position of fragility in the future. Guarding against that will require a replenishment, a rebuilding of all the capitals I've mentioned, including significantly the often overlooked capital or endowment that is held. I've suggested one or two ways in which that rebuilding or replenishment might take place. Why is it always us, let me end optimistic. It need not be. The diagnosis is pretty clear. The prescription is also pretty clear. We can avoid this and for me we absolutely should. Thank you everyone for listening.

Download the slides

The UK continues to feel the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, both through its impact on the nation’s health, as well as the prolonged impact on the UK economy.

Yet despite this, there isn’t enough attention on boosting population health, the NHS and social care to build resilience to future shocks and support economic recovery.

For the 2022 REAL challenge lecture, Andy Haldane, Chief Executive of the RSA and former Chief Economist at the Bank of England, explored the relationship between health and wealth.

He drew lessons from the pandemic and argued for a more holistic economic growth strategy where health and wealth are inextricably linked.

He was joined by a panel of respondents, Jordan Cummins, Programme Director of Health, Confederation of British Industry (CBI), Dr Ricky Kanabar, Assistant Professor of Social Policy, University of Bath and Jill Rutter, Senior Fellow, Institute for Government.

The event was chaired by Dr Jennifer Dixon, Chief Executive of the Health Foundation.

Speaker

Andy Haldane is Chief Executive of the Royal Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA) and was formerly Chief Economist at the Bank of England and a member of the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee.

Among other positions, he is Honorary Professor at the Universities of Nottingham, Exeter and Manchester, a visiting Professor at King’s College London, a visiting Fellow at Nuffield College Oxford and a Fellow of the RSA and the Academy of Social Sciences.

Andy is Founder of the charity Pro Bono Economics, Vice-Chair of the charity National Numeracy, Co-Chair of the City of London Task-Force on Social Mobility and Chair of the National Numeracy Leadership Council.

He has authored around 200 articles and 4 books.

Chair

Jennifer was Chief Executive of the Nuffield Trust from 2008 to 2013. Prior to this, she was Director of Policy at The King’s Fund and was the policy advisor to the Chief Executive of the National Health Service between 1998 and 2000. Jennifer has undertaken research and written widely on health care reform both in the UK and internationally.

Originally trained in medicine, Jennifer practised mainly paediatric medicine, prior to a career in policy analysis. She has a Master’s in public health and a PhD in health services research from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. In 1990–91, Jennifer was a Harkness Fellow in New York.

Jennifer has served as a Board member on several national regulatory bodies: the Health Care Commission 2004–2009; the Audit Commission 2003–2012; and the Care Quality Commission 2013–2016. She has led two national inquiries for government: on the setting up of published ratings of quality of NHS and social care providers in England (2013); and on the setting up of ratings for general practices (2015). She was also a member of the Parliamentary Review Panel for the Welsh Assembly Government advising on the future strategy for the NHS and social care in Wales (2017–2018).

In 2009, Jennifer was elected a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, and in 2019 was elected as a fellow of the Academy of Medical Sciences. She was awarded a CBE for services to public health in 2013, and a Doctor of Science from Bristol University in 2016. She has held visiting professorships at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, the London School of Economics, and Imperial College Business School.

Panellists

Jordan joined the CBI In 2014, following a role with the MoJ in HMPS. In the seven years with the CBI, Jordan has held both commercial and policy roles, including Assistant London Director and Head of Policy. In December 2021, he became the CBI’s first Health Director, leading a new team and the organisation’s engagement across DHSC, NHS, BEIS, OHID, UKHSA and HMT on industry priorities in health and life sciences. Jordan studied Law and Public Policy & Management at undergraduate and postgraduate levels, respectively. Jordan lives in South London and is active within local politics.

Ricky is currently an assistant professor of social policy at the University of Bath. His research interests focus on issues related to social mobility, ageing and health. His projects use quantitative methods to better to understand important public policy issues. Ricky’s research has featured in various international peer-reviewed journals, policy reports and the media. He has worked with multiple government departments in England, the Scottish and Welsh Governments and international organisations such as the OECD.

Jill Rutter is a former senior civil servant and now Senior Fellow at the Institute for Government and Senior Research Fellow at UK in a Changing Europe. Her government roles were in HM Treasury, No. 10 and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more